Quick Links

What is debt recycling?

What are the tax implications of debt recycling?

Debt recycling vs borrowing to invest

What can you debt recycle?

Offset vs redraw

What to watch out for

Debt recycling steps

Interest only or Principal & Interest loan

High-yield or low-yield investments for debt recycling

When should you not debt recycle

The end game

Is debt recycling legal?

Debt recycling vs concessional contributions to super

What is debt recycling?

Debt recycling is a strategy to convert (recycle) your non-deductible debt into tax-deductible debt.

Whether interest is tax-deductible does not depend on what you borrow from. It depends on what the borrowed money is used for.

A PPOR (principal place of residence – the house you live in) is not an investment, so the interest on a loan used for your PPOR is not tax-deductible.

In contrast, the interest on a loan used for investments is tax-deductible.

The way debt recycling works is that initially, the loan interest on your home is not tax deductible since it is not an investment. Then, if you pay part of the loan down, you reduce that non-deductible debt. After that, if you then borrow that same amount back out and purchase investments (e.g., shares or property), the interest on that portion of the loan that is used to purchase investments is tax-deductible. So you have converted (recycled) that portion of the loan from non-deductible to deductible, and the interest on that portion of your loan is tax-deductible for the life of the loan while it is invested in income-producing assets.

Another way to explain it is that if you have spare cash to invest, rather than investing directly, you can send it on a detour of paying down the loan and drawing it back out before investing, and doing will mean that portion of your debt is tax-deductible. So, in addition to the return you get from the investment, you get an additional return through a personal tax deduction on the loan interest.

Let’s say you had a $100,000 loan on your home with an interest rate of 4%. That means you are paying $4,000 each year in interest. If you were able to convert that to a tax-deductible loan, you would be able to take that $4,000 off your taxable income and if your marginal tax rate was 30%, you would pay 30% x $4,000 = $1,200 less tax each year. The result is that the government effectively pays for 1.2% of that 4% interest, and you are only paying 2.8% interest.

For those with a home loan, debt recycling is one of the best tax-minimisation strategies outside of super.

In addition to the benefit of reducing tax, debt recycling also helps you build an investment portfolio outside of super that can continue to provide passive income once your home is paid off, and which can supplement your superannuation while also being accessible before you can access super.

What are the tax implications of debt recycling?

Debt recycling essentially reduces your effective borrowing rate by your marginal tax rate.

The calculation in the table below is such that if your marginal tax rate (MTR) is 32% (including the 2% Medicare levy), and your loan rate is 4%, then your effective interest rate is 4% x (1-32%) = 2.72%

Effective Borrowing Rate When Debt Recycling

| Loan Interest Rate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MTR (inc. ML) | 4% | 5% | 6% |

| 32% | 2.72 % | 3.40 % | 4.08 % |

| 39% | 2.44 % | 3.05 % | 3.66 % |

| 47% | 2.12 % | 2.65 % | 3.18 % |

As you can see, the higher the marginal tax rate, the more of a benefit because those on a higher marginal tax rate are paying so much more tax that more is deductible. This provides an effective way to borrow very cheaply for those on high marginal tax rates, enabling a higher after-tax return on your investment, and it is your post-tax return that matters.

Debt recycling vs borrowing to invest

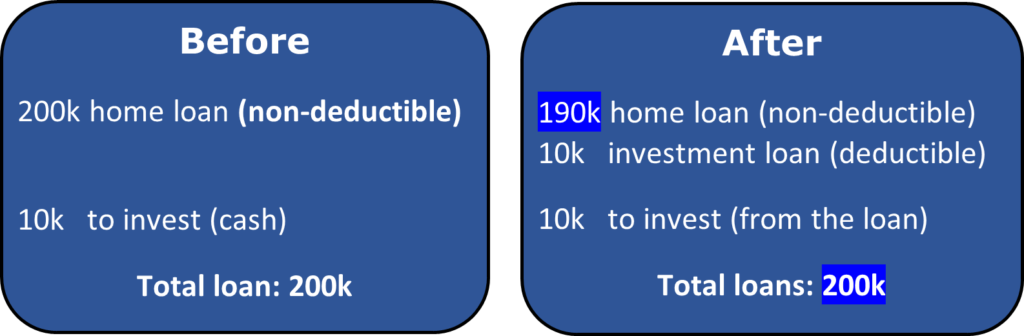

Debt recycling is simply converting existing non-deductible debt into tax-deductible debt.

For instance, if you have $10,000 to invest – instead of investing directly, you pay down the loan, borrow it back out, and then invest.

Whether you’ve debt recycled or invested without paying down the loan and drawing it back out first, you still have the same amount borrowed and bearing interest, but in the case where you pay it into the loan and borrow it out first, part of the loan has become tax-deductible.

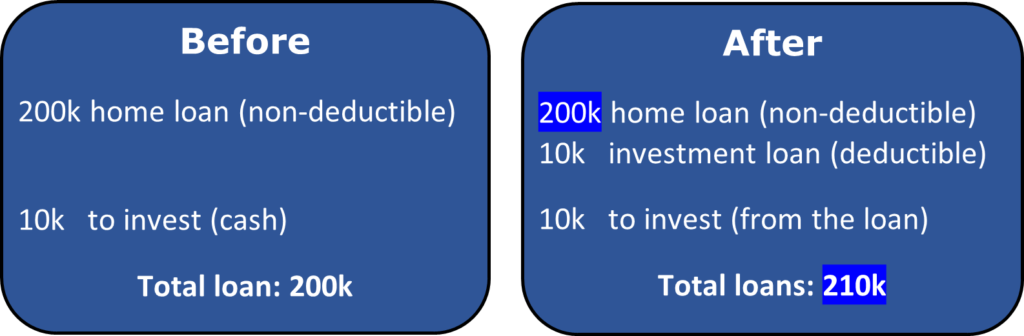

Leveraging (i.e., borrowing to invest), on the other hand, increases your amount borrowed and bearing interest. This is not the same as debt recycling, where you are recycling non-deductible debt into deductible debt.

Debt recycling:

Same total loan amount before and after, but now part is tax-deductible.

Leveraging:

Results in a higher total loan balance.

This is an important distinction because:

- leveraging increases your risk as you have more money invested and more debt that you need to service loan repayments on, whereas

- debt recycling does not increase your risk as you have the same amount of money invested and the same amount of debt that you were already servicing.

What confuses many people is when they have money in the offset and then decide to use it for investing. Technically, in this case, you would debt recycle so that you pay that offset money into the loan and then borrow it out to invest, but really what you are doing by taking it out of the offset is increasing the amount of money that is generating interest payable on the loan each month, making it more accurate to consider it leveraging. The distinction may seem subtle, but it is fundamental in understanding the consequences of your strategy.

The decision of whether to use your money from the offset rather than leave it there offsetting the loan is a decision on leveraging.

However, once you have made the decision to invest outside super – provided you have non-deductible debt – it would be silly not to debt recycle since you end up with the same amount of debt (and therefore risk), but now with tax deductions (i.e., free money each month for the life of the loan).

An alternative option if you have already decided to take money out of your offset to invest

If you have already decided to take money out of your offset to invest, ordinarily, debt recycling makes sense. However, if you have equity in your home that you are able to borrow from, then borrowing to invest with the same amount that you were going to debt recycle with from your offset while leaving your money in the offset would result in the same outcome [1], as you would have the same amount of money that is generating interest payable on the loan each month.

However, extracting equity in your home to use for investing would allow you to retain your cash in the offset as an emergency fund without the opportunity cost of holding cash in a savings account. This is also known as ‘springy debt‘.

[1] This assumes the same interest rate. However, when you cash-out equity from your home, the bank will ask what it is for, and if you are borrowing to invest, you will typically get a higher interest rate. For smaller amounts (50-100k), you may be able to cash-out some equity, giving the reason as being for a renovation or home extension and get the same non-investment interest rate.

What can you debt recycle?

You can debt recycle any non-deductible debt, but it doesn’t make sense to recycle debt on a depreciating asset, so it is typically a home loan.

What you invest in with the recycled debt must be income-producing, so the two typical investments are shares and investment property.

As property is a lumpy asset (you pay a very large amount upfront), you would pay down your deductible debt and draw that out to be used to purchase the investment property, and that is as much as you can recycle into that specific asset. You could then do it with another property.

A good example of this is where you have cash that you plan to use for buying an investment property. Just before you are ready to pay for the investment property, you would pay it into your home loan and draw it right back out and use the funds for the purchase of your investment property to make that portion of your home loan tax-deductible for the life of the loan.

Shares, on the other hand, can be purchased in small chunks, so you can pay down your deductible debt and draw it out to purchase shares of that value. Then, when you have more spare cash, you can recycle into another tranche of shares, and so on, until all of your home loan has been recycled.

Offset vs redraw

With a home loan, you can put spare cash to work earning a higher interest rate than a bank account by using either a redraw facility or an offset account. Both of them reduce the interest you pay on the loan, but there is a difference.

An offset account is a regular savings account. Any money in there is still your money. When you take it out and use it for investing, nothing has changed with regard to the tax deductibility of your loan interest.

In contrast, paying money into a redraw facility is paying down the loan. It is secured extra repayments for the bank. This means that the bank can remove access to it since it is their money. When you take money out, it is considered a new loan for tax purposes. If this newly borrowed money is used to purchase income-producing assets, the interest is tax-deductible, otherwise it is not.

For this reason, an offset is used for savings you want to retain access to, and a redraw facility is used for debt recycling when you are ready to debt recycle.

More here on the difference between a redraw vs offset.

What to watch out for

The basic concept of debt recycling is very simple – pay money into a loan and borrow it out to purchase income-producing assets (i.e., investments). But there are a lot of details and it is easy to make a mistake that can cost you the deductibility.

1. Mixed loans

While technically you can use a redraw against your main home loan to pay it down and borrow it out to recycle your debt from non-deductible into deductible, you should instead contact your bank and pull your money out into a new separate loan split [1] so that the money you pay off and then pull out for investing is not mixed with funds that you draw out for personal use.

Mixing is where you use some of your funds for investing and some for personal use.

Mixing is not only going to be a nightmare for your accountant trying to apportion it to figure out how much you can claim against your personal income tax, but if it cannot be clearly apportioned, you may lose the tax destructibility entirely. If you find this out in an audit in 10 years, that’s likely in the tens of thousands of dollars you would have to pay back.

The next issue of mixing is that when you pay back some of it into the redraw, it may be considered to be paid back in proportional parts. So if you used 20% for personal use, 40% for an investment property deposit, and 40% for shares, and if you paid back 20% thinking it was for personal use and that you can now claim 100% interest from then on, if you get audited you may get a rude shock to find out that 20% of the remaining loan continued to be considered for personal use.

[1] A separate loan split is a separate loan with its own loan number that you will see as a different line item when you log into your internet banking with your lender. With some banks, you can split your loan over the phone (or even online), whereas others will require paperwork.

2. Not having a direct connection from the borrowing to the use of the funds

To successfully be able to claim a tax deduction, you must be able to demonstrate a direct link from the borrowed funds to the use of those funds that are to be used to purchase income-producing assets.

While the ATO’s own ruling states that rigid tracing of funds are not always necessary to claim a deduction, in the Domjan case, the ATO successfully argued that placing borrowed money into a savings account with other personal funds where a personal cheque was written from, broke the link that proves the funds were borrowed for tax-deductible purposes.

Always draw funds directly from the loan to an empty account that is only used for that specific investment purpose and not for other purposes. Do not use some of those drawn out funds for personal use and some for investment. In the case of debt recycling with shares, it is best to draw it out directly into an empty brokerage account without any pit stops in an intermediary account.

Furthermore, cash that has been drawn out yet remains in that account for a lengthy period of time before being used may be questionable as far as showing a direct connection from the borrowing to the use of the funds. So leave the money in the redraw (or don’t even use the redraw yet) until you are ready to move it from the redraw to a clean account to purchase income-producing assets in a timely manner.

3. Investments that do not produce assessable income

To successfully be able to claim a tax deduction, you must be able to demonstrate that the money is used to purchase investments that are income-producing, or have the expectation of producing income.

For instance, if you borrow to buy land without anyone renting it, and therefore, there is no income being produced, you are unlikely to be able to claim a tax deduction on that loan.

Similarly, if you buy something like AFI/ARGO/WHF/etc. and elect to use a Dividend Substitution Share Plan (DSSP) or Bonus Share Plan (BSP) offered by these investment companies to receive additional shares in place of distributions, you are unlikely to be able to claim a tax deduction for that loan.

However, interest will still be deductible even if there is no income, provided you can prove that it was acquired for the purposes of producing income (Steele v FCT (1999) ATC 4242). So if you purchase shares that typically pay distributions and one year it unexpectedly doesn’t, the interest is likely to be tax deductible. An example is during COVID where some shares do not pay dividends, but they ordinarily do, and it is likely that the loan interest is still tax deductible.

Summary

To avoid mixing and breaking the link between the borrowing and the use of the funds:

- Get a separate new loan split for each new purpose so that they’re clearly segregated.

- Have that loan split come with its own separate redraw facility.

- When it is to be used for investing:

- Pay the redraw down one time and in full.

- Ideally, draw it directly to where it will be used for only that investment. Do not send it to any other account in the interim, and certainly not somewhere that it will be mixed with any other money. This will ensure the link is clear as to what the borrowed funds are used for. If buying shares, draw it directly from the redraw into your brokerage account and without cash in the brokerage account to avoid mixing (and preferably in a separate brokerage account to what you don’t use for debt recycling). Invest it in a timely manner once in the brokerage account to minimise/avoid non-deductible interest being charged on the loan in the meantime.

- While redraw paydown must be done in one time and in full, you can redraw it out to invest in stages (but it should be used for the same purpose).

Debt recycling steps

The steps for debt recycling into a share portfolio are:

- Split your home loan. For instance, you might split a $500k home loan into a 50k loan split (with redraw) and a 450k loan split with an offset.

- Save any spare cash into the offset account to retain access to it until you are ready to recycle it.

- Once you have the full loan split ($50,000 in this example) and are ready to debt recycle, transfer all but $1 (so, $49,999) from the offset to the 50k loan split’s redraw facility and immediately redraw it directly out to the empty cash account of a share brokerage account that is used only for debt recycling. [1]

- Invest the money from your brokerage account into income-producing assets.

Consequently:

- The $50k loan has not been mixed with any other funds.

- You have a direct connection from the borrowing of the $50k to the use of funds.

- The funds are being used for income producing assets.

- The interest on the $50k loan split is now, therefore, tax deductible.

- The interest on the $450k loan split is not tax deductible – yet.

- Once you have another $50k saved into your offset, repeat again with another separate 50k loan split.

Note that you could have initially created more loan splits to avoid having to apply to the bank to split it frequently. You can also create smaller loan splits if you want your money to be invested sooner or a larger loan split if you had more money.

[1] The reason for not paying down the full loan split (and leaving $1) is that some banks close the loan split when it is fully paid off. That is also the reason for waiting until you are ready and drawing it back out immediately – because if you have under a certain balance for a defined length of time (which varies by lender) they also may remove the ability to redraw it back out.

Interest only or Principal & Interest loan

The general rule of thumb is to go with Interest Only (IO) loans on tax-deductible debt to maintain the maximum tax deductions over time. So, you would use that on the debt recycled split(s).

Since about 2017 when the government tightened up lending rules due to very high total levels of household debt to encourage people to start paying down debt, they pushed banks to increase rates on IO loans, so IO loans are often about 0.5% higher, which is not a small amount of money. 0.5% on a $400,000 loan is $2,000 p.a. that could have gone to paying down your loan. So, typically, you would use P&I on your non-deductible split.

Calculating the best option for your debt recycled split is a challenge because by using P&I, you lose the tax deduction for an unknown number of years – just to be aware that all else equal, you generally want IO on your deductible debt to maintain the maximum tax deductions for as long as possible.

High-yield or low-yield investments for debt recycling

In addition to using your regular savings to debt recycle, the income from your investments should also be recycled to speed up the recycling process. So be sure to turn off your Dividend Reinvestment Plan (DRP) if you have turned it on and instead, have distributions paid out to you, and add that to your savings that you are building up for your next debt recycling tranche.

This brings us to the question of whether to use high-yield or low-yield investments for debt recycling.

Earlier, we explained the difference between debt recycling and borrowing to invest (leveraging). Another reason to clearly differentiate your intention of debt recycling vs leveraging is that they lead to different investment strategies, which leads to different implementations for each of those strategies.

With debt recycling, you want to pay down your home loan in a manner that converts more of your loan from non-deductible debt into deductible debt. You also may want to avoid reducing your cash flow. High yielding investments with a principal and interest loan achieve both of these goals.

Whereas with leveraging, you are more likely to want to maintain the loan amount to maximise your tax deductions and investment returns at the expense of your cash flow, so you may want to go with an interest only loan and high-growth/low-yielding investments.

While high yielding shares do not generally result in increased expected total returns, with debt recycling you want to pay down your home loan in a manner that converts more of your loan from non-deductible debt into deductible debt, and high yielding investments achieve this goal.

The issue with using high yielding shares is that they reduce diversification, particularly since high yielding shares typically mean more shares from Australian companies with franked dividends.

One way to achieve this acceleration of debt recycling without reducing your global diversification is to use more Australian shares for debt recycling (which tends to have a larger income component, which is furthered by franking credits) and balance it by using more international shares within your super.

However, it is important to note that if you can afford the negative cashflow to provide the benefit of negative gearing (especially for those on a high marginal tax rate), you may want to go with high-growth/low-yielding investments even when debt recycling and use an interest-only loan on the debt recycled loan splits and a principal and interest loan on the non-deductible loan split.

When should you not debt recycle

There are a few reasons not to debt recycle.

1. You don’t have the risk tolerance for investing

All investment carries risk, and two important parts of your tolerance for investing are

- Your ability to take risk – your ability to leave your money invested (not needing access to it).

- Your willingness to take risk – your ability to stay calm during times of high volatility – when the value of your investment takes a dive.

A lot of people also have a fear of investing because don’t understand the difference between single-asset risk and market risk.

If you are not yet comfortable with investment risk, which includes being comfortable with debt, then debt recycling may be something you should consider later after you have learned more about investment risk and feel more comfortable with your investment plan.

2. You do not have a long investment time horizon.

Investing is a long-term venture due to the risk inherent in investing. The reason you get a higher expected return with investing is due to the risk premium. If you don’t have sufficient time to ride out the short-term volatility, you may end up selling your investment at a low after it is worth less than what you purchased it for. So, if you don’t have a sufficient investment time horizon, you should not be investing, and that means you should not be debt recycling.

3. You are going to turn your home into an IP

You want as much of your total loan interest to be tax deductible as possible. However, when you pay down your future IP (investment property), you cannot restore the tax deductibility on the property that will become an IP by moving your shares to debt recycle it on your new PPOR’s non-deductible debt.

Let’s say you plan to upgrade your current PPOR in two years and buy a new PPOR to keep for the long term of 10+ years and keep PPOR #1 as an IP. You want to maximise your existing debt on your future IP (PPOR #1) because the loan interest becomes tax deductible for the life of that loan while that is an investment and recycle your non-deductible debt on the new PPOR so that portion becomes tax deductible for the life of that loan.

Had you paid down PPOR #1, even if you sell the shares to pay back that loan (with the intention of debt recycling on your new PPOR), you cannot restore the original deductibility on that portion of the loan. The tax deductibility against the portion of the IP loan that was paid down for debt recycling is only deductible while it is used for income-producing assets.

This is the same concept explained in the redraw vs offset article of why to put spare cash into an offset and not a redraw to avoid paying down the loan if you are going to turn your PPOR into an IP.

The end game

The goal of debt recycling is to convert your entire home loan from non-deductible debt to deductible debt and you also have an income-producing investment portfolio in addition to your super.

Once that is done, you have the option to either:

- Start paying down that deductible debt so that you end up with a paid-off home along with an ongoing passive income from your share portfolio (using ongoing savings plus distributions); or

- Leave it alone since it is ‘good debt’ (i.e., tax deductible and growing in value) and contribute to a separate share account to grow your total asset base further and retire your home loan debt at a later time.

It depends on your risk tolerance (including comfort with debt) and what you are trying to achieve at that time.

Is debt recycling legal?

Tax legalities can be grouped into three categories:

- Tax planning – legally arranging tax affairs for a favourable tax result

- Tax avoidance – minimising tax while remaining within the law but exploiting a loophole in the law

- Tax evasion – illegitimate means to reduce tax

The ATO has come up with anti-avoidance measures to stop tax avoidance, known as Part IVA (pronounced “Part four A”) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936

The anti-avoidance rules of Part IVA are for schemes where the “sole or dominant purpose“ is to derive a tax benefit.

You will need to speak to an accountant (which I am not) to get a definitive answer, but my understanding is that Part IVA does not apply to debt recycling because the tax deduction on interest is incidental to using home equity to invest in other assets, which is the primary purpose of this strategy.

Where there might be an issue is if you already have a share portfolio, sell it, put it into the loan, draw it out, and invest in exactly the same investments. Comments I’ve heard for dealing with this include:

- Rebuying different investments such that the sole or dominant purpose is to change your investment strategy, and the tax deduction is incidental to the intended purpose rather than being the sole or dominant purpose.

- If you have cash available (for example, an emergency fund), pay down the loan and debt recycle into investments and then sell your shares and replace your cash. This breaks the link between selling existing shares and debt recycling into the same shares.

- Similarly, if you sold your shares and waited for a sufficient time to break the link (e.g., a month), you could potentially argue that you were sold the shares for other reasons (e.g., thought there was a market crash coming and later the economic forecast changed – this is obviously less believable if you sell and ‘change your mind’ a day later).

Whatever your reason, it must be arguable that there is another purposes such that the sole and dominant purpose is not to derive a tax benefit.

Debt recycling vs concessional contributions to super

Concessional contributions are miles ahead of debt recycling in terms of wealth creation. This is because, with concessional contributions, you essentially have an instant return before the compounding even begins of up to 60% [1]. Then you get the compounding on both your initial investment as well as the additional 60%.

[1] 60% is for those on the 47% marginal tax rate (including Medicare levy). See the above link for other marginal tax rates.

To put this into perspective, people often mention the higher returns of property than a share portfolio due to property being leveraged at 400% of your initial input, but even that – along with the massively higher risk – does not outperform the compounding of your super investment when it comes with a 30% boost from day one.

The downside of super contributions is that they are locked up until preservation age, so if you want to use those funds before that (for instance, for early retirement or helping to pay down your home a little sooner to move to reduced work for a better work-life balance), then super is not an option, and debt recycling becomes a good option to consider.

My suggestion would be to consider doing a bit of both. Some additional concessional contributions each year will result in a massive increase in wealth for the last 3 decades of life from age 60, and some additional investment outside super (via debt recycling, if you have a home loan) will build a passive income outside super so that you have the option of retiring or semi-retiring sooner.