A risk premium exists when an asset has a known risk, and buyers price the asset lower by not being willing to pay as much as for more stable assets to ensure that their expected return is higher to compensate for the higher risk.

‘Expected return’ is the weighted average return of all the possible outcomes.

However, even when paying less to make up for the times that the risk eventuates and the investment underperforms, an investor is not going to pay for a higher risk asset to get the same expected return. If you were looking at the same expected return of a safer asset as for a riskier asset, of course you would choose the safer asset every time. You aren’t going to go for an investment with higher volatility for the same expected return. The incentive for higher risk assets is paying even less still below the amount that would give you the same expected return as an incentive to take on the higher risk. This means that your expected return is higher, even after accounting for the times the risk shows up.

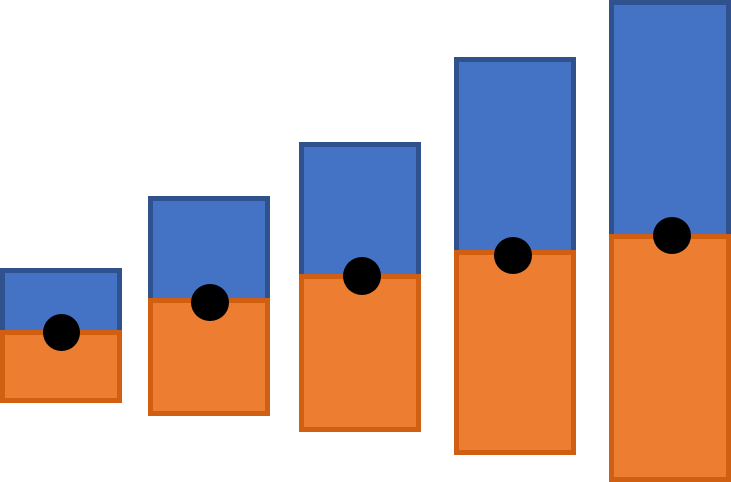

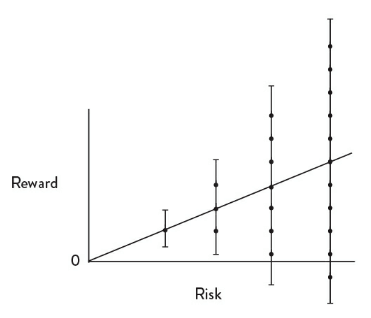

Let’s see this pictorially from an image in an earlier article.

On the left, you would have low-risk investments, starting with cash and short-term government bonds, where your asset value fluctuates very little or not at all. As you move further right to more risky investments such as stocks, along with the higher risk (risk = larger range of possible outcomes), your expected return (the point on the diagonal line) increases. The expected return is like a weighted average of all potential outcomes. To get this higher expected return, you face the risk of any of the range of possible returns.

With higher risk investments such as stocks, the average return over very long periods tends to be higher, but this higher risk can mean higher highs and lower lows.

What if there was a way to lower or remove the risk?

If we could find a way to remove this risk, the market would no longer price the assets at a discount. They would be priced higher, and as a consequence, your expected return would fall.

This is why risk and expected return are and will always be linked.

You may be frustrated that to get good returns, you have to tolerate higher risk, or you may be joyful that there is a way to get higher returns, but these are two sides of the same coin – the yin and yang that is risk and return.

Higher risk asset subclasses

Beyond the risk within the broad global stock market, there are specific risks inherent in certain subclasses of stocks. As a consequence, and for the same reason explained above, these have a higher expected return than the broader stock market.

Emerging markets have political instability, massive corruption, trade wars, and a host of other problems. At any time, a company in an emerging country could face these problems resulting in lower returns in the future. To account for this, investors are not willing to pay the same price for an equivalent share in a more stable country.

It’s the same with small companies, which are more likely to go under than larger, more established companies. The risk is priced-in by way of investors only being willing to pay less for shares in those companies.

Another example is undervalued companies (called ‘value stocks’). In an efficient market, they’re not accidentally mispriced. Investors have priced them lower due to one or more known risks. Maybe the sector is doing poorly due to the current state of the economy. Maybe the sector has been targeted for wide-scale fraud and is being investigated by ASIC and facing potentially enormous fines. Maybe in an upcoming election, there is a policy on the table to remove tax advantages for these companies.

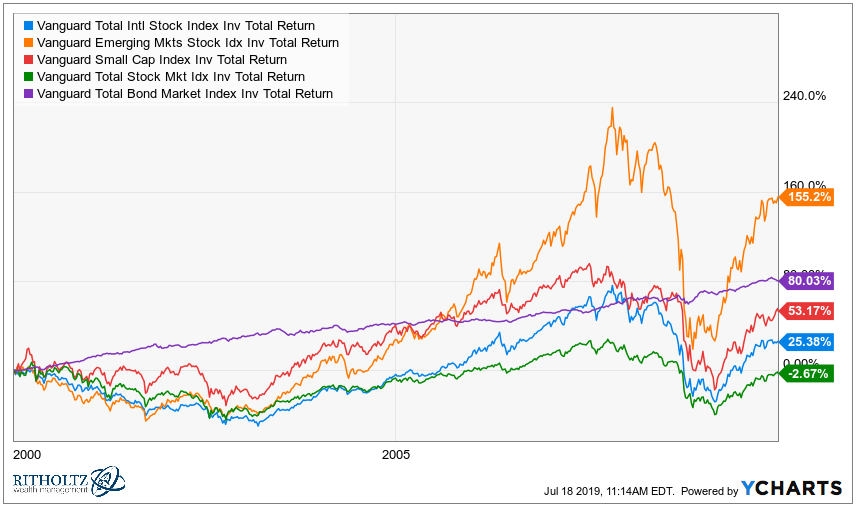

What all of this means is that the average return over very long periods tends to be higher, but this higher risk can mean higher highs and lower lows, and these can last for very long periods such as emerging markets in the past decade which returned around 6.5% annualised compared 12.5% annualised for developed markets. That’s a difference over 10 years of turning $100,000 into $187,000 instead of $324,000.

Of course, this eventually balances out with periods where it does incredibly well, such as the previous decade where emerging markets crushed developed markets.

Source: A Wealth Of Common Sense

So, as you can see, there’s no free lunch. You’re paying for these higher expected returns with higher risk.

However, there is, in fact, a portfolio-wide free lunch when you include a small amount of these with the rest of your equities because they move up and down at different times, and this is why diversification is known as the only free lunch.

It’s a mistake to think that people who invest in these higher-risk asset subclasses, such as emerging markets and small caps, have no idea of the systemic problems in these asset classes and that somehow you know more than the rest of the market which has priced these equities.

If you do decide to include any of these higher-risk asset subclasses beyond market weight, be aware of the risks. If you’re the type of investor to consider changing your allocation and abandoning these based on potentially excruciatingly long or sharp periods of underperformance, then these asset classes are not for you. Not only do you need to tolerate these periods to get the return, but you should be itching to buy more of them when they’re underperforming. If you don’t understand what you’re buying and aren’t 100% committed as a permanent allocation (i.e. for decades), you’ll eventually sell when it underperforms, and your portfolio will permanently underperform the broader market.

Lower risk asset subclasses

Just as there are higher risk subclasses, there are also lower risk subclasses. Utilities is a well known one. It tends to move with the stock market but with smaller ups and downs, partly because the greater population needs utilities in all market conditions. The same thing happens with large, established companies. They have more money to throw at problems and are more able to weather tough market conditions. Of course, as explained earlier, there’s no free lunch here. The consequence is a lower expected return commensurate with the lower risk by way of buyers and sellers in the market pricing in less of a discount.

When you don’t get a higher return with a higher risk

A final note – you don’t automatically get a higher expected return with higher risk. There is compensated risk and uncompensated risk. Stock and bonds are priced to compensate for the amount of risk. Gold is one example of an asset that has no real (inflation-adjusted) return but is highly volatile, so the risk with gold is an uncompensated risk. Another example is currency risk, which doesn’t improve your expected returns. A further example is buying individual stocks. A single stock will have a much higher range of possible returns than buying the entire market or sector, but the expected return on a single stock hasn’t increased.