For the purposes of this article, LIC’s will refer to the older LICs (AFI, ARG, MLT) and not the broad range of all LICs.

Usefulness of LIC’s

Before indexing, you had a choice between picking your own stocks or actively managed funds. Neither of these options are particularly attractive.

To pick your own stocks, you need to get down and dirty and learn all about each company’s finances. Not only that, you need to actually understand it and try to predict if it will do well in the future.

The other option was having faith in a fund manager to pick your funds. Having faith when it comes to your money is a tough call. If you’re like me, you don’t want to rely on hope for your financial security.

This is where LIC’s came in. They trade infrequently and are somewhat of an index proxy. Essentially, they are the closest thing to an index fund that was available. Like index funds of today, they are also low cost.

They still have some downsides to index funds, so I don’t see much point in LIC’s today when there is a better alternative, but I certainly don’t consider LIC’s to be a bad investment, they’re just not anything particularly special. So while it is probably fine to go ahead and use LIC’s in place of your Australian asset allocation (not your total asset allocation), the arguments put forward by LIC advocates, unfortunately, are almost entirely nonsense. I don’t see how anyone can make an educated decision when they are being fed half-truths designed to convince you rather than educate you.

So, let’s take a look at the arguments.

You can just live off dividends and not worry about the movement of the markets

1. On dividends –

-

- Dividends are not company earnings. Along with the fact that from earnings, a company can pay out 20% or 80% or none, dividends also include payouts from sold assets and exclude profits distributed to shareholders through buybacks. As a result, dividends give little-to-no indication of either the business’s income or the overall return.

- If you use all your high yield to live off and it’s above a safe withdrawal rate, you will unknowingly deplete your portfolio. Dividends are not free separate money – they come out of your total return. If a company is gifted money, the value has gone up by that amount. Similarly, paying out dividends comes out of the value of the company.

2. On investing only in LIC’s to get high yield which international companies do not provide –

-

- For international (non-Australian) shares, companies often distribute earnings as a share buyback to boost up the price.

For example, let’s say there are currently 10 shares valued at $8 each and the company decides to distribute $16 of earnings back to investors — they buy back 2 shares, and now there are 8 shares at $10 each, so the value of each of your shares have increased $2 as a way for the company to distribute the $2 instead of paying it out as cash dividends.

Most countries don’t have franking credits, so companies often distribute earnings as share buybacks for the benefit of their investors to pay less tax (profits are then taxed with capital gains discount).

As a result, even though there is less paid out as dividends for international shares, money is still being distributed to shareholders via an increase in share price as a result of share buybacks, so lower dividends don’t mean company profits have not been distributed back to shareholders.

- For international (non-Australian) shares, companies often distribute earnings as a share buyback to boost up the price.

Besides this –

-

- You face idiosyncratic risk by not investing in the other 97.5% of the investable world.

- You face concentration risk by investing in the same country as your property and job.

- The often-quoted fact that Australian companies sell overseas and therefore have overseas exposure is not a valid reason not to diversify into the other 97.5% of the investable world. Due to the massive overweight of finance and mining taking up half the entire market, the Australian stock market is underweight in pretty much everything else. Not only that, these sectors are highly cyclical, resulting in high volatility. Having global revenue sources doesn’t give you the global diversification benefits of actually owning non-Australian stocks, which would have a more even weighting of the many other sectors, and this can be seen in this Vanguard paper on global diversification showing that the global portfolio had far lower volatility than all other individual countries, and the volatility was almost half that of the Australian market.

This is a visual display of single-country risk. It appears to be just price without distributions but that doesn’t take away from what can easily result from single country risk.

3. On ignoring the movements of the markets –

When dividend investors have exhausted every other attempt at defending dividend investing, their final argument is that focusing on dividends offers a behavioural benefit that allows you to remain invested during market turbulence, therefore it still has value.

The problem with feeling good at the expense of facing reality is that one day there may be a sustained market decline and a long drawn out recovery, and you will find that dividend-focused shares are not a bond proxy.

This article on what a bear market feels like points out that

If we start seeing property prices go down, unemployment goes up, and banks start taking losses then they’re going to be cutting their dividends pretty sharpish which will likely push their share prices lower. In the last crisis in the US the major banks weren’t allowed to pay out dividends for quite some time, it’s not unthinkable that the same thing could happen here.

And this morningstar article explains that regulators forced UK banks to suspend dividend payments of banks and to cancel any dividend payments outstanding from the previous year to ensure that enough cash was available for those with cash in their bank accounts during coronavirus when an enormous number of businesses were shut, resulting in mass unemployment.

This should give you some pause to consider the danger of assuming historically strong dividend payers are a bond proxy that will provide you with safe income during a downturn. If the market doesn’t recover before your favourite LIC’s cash reserves run out, you would be forced to sell down your stocks when they are low, drawing down and depleting your portfolio faster and for longer due to the fact that a recession hits earnings of all businesses, resulting in an increased risk of running out of money in retirement, whereas if you had faced reality, you would have had a more appropriate allocation of bonds which would have lowered this risk. The fact that fixed-income assets have low returns doesn’t mean they have no use, and assuming LICs are a bond proxy is a mistake of potentially devastating proportion.

Deluding yourself to avoid facing reality and consequently failing to prepare for potential risks is not a benefit — it’s a disadvantage.

Active management – LIC’s can avoid the ‘crap’ companies with poor future prospects

Far too much evidence that fund managers fail to do this.

Due to the Pareto principle, most of the future performance will come from a disproportionately small portion of the market which you cannot know in advance, and it is much easier to miss these few companies resulting in lower performance than just holding everything.

Add to this SPIVA reports showing that over sufficiently long periods, active management fails to meet the index returns over 80% of the time after accounting for fees, and you can be sure that if anyone tells you that LIC’s provide a benefit in being able to avoid the ‘rubbish’ in the index, they’re full of crap.

In fact, not only is this not a benefit, it is a major risk – management risk – which is an uncompensated risk.

They can leave out mining companies because they have poor performance

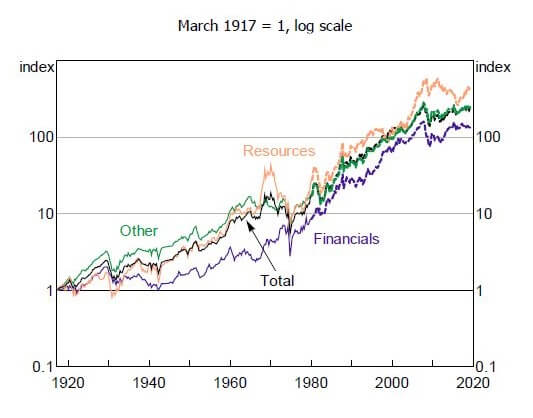

As you can see in the image below from RBA data, over the past century, the mining sector’s performance has been very much in-line with industrials and the graph shown repeatedly to “prove” the underperformance of mining happens to begin at the peak of a massive mining boom. When you begin from a peak, obviously it will distort the data to make it appear to have lower performance going forward as it reverts to its long-running mean.

They can leave out mining companies because they pay out very little in dividends

Provided the total return is not lower, it makes no difference whether returns come from price increases or dividends. There is nothing stopping you from selling some to release some cash.

They can leave out REITs because their performance is poor

REITS have outperformed stocks for the past 50 years (Link 1) (Link 2) (Link 3)

They can leave out REITs because, by law, they are required to pay out at least 90% of their net income, so they can’t grow their asset base like industrial companies can

There are two fallacies here.

Firstly, yes, it’s true that REITs are legally required to pay out at least 90% of their earnings as dividends, but you can buy more shares with the higher dividends and grow your asset base yourself. Think about it – if Australian shares grow 4% and pay out 4% dividends, and REITs grow 2% and pay out 6% dividends, there’s no reason why you can’t take 2% of the 6% dividends and reinvest it, thereby growing your asset base and therefore your dividends.

Secondly, while you can expect growth to be lower due to paying out more of the earnings (which you can reinvest yourself to grow your assets), it’s a false conclusion to say that their asset base cannot grow. Like many industrial companies that use leverage to lever up both their risk and return, so do REITs. This can be seen in the above link showing that over the past 50 years, REITs have outperformed equities on a total return basis. [1]

[1] Past performance is not indicative of future performance.

LIC’s pay out more franking credits – 100% of the dividends are franked

70-80% of the index’s dividends are franked.

The last 20-30% that you’re getting franking credits for in an LIC is because the tax has already been paid by the LIC out of funds that you would have received and paid yourself anyway. It isn’t free money.

LIC’s smooth dividends

Unlike ETFs and managed funds, which are trust structures, an LIC is a company structure, and therefore can retain profits rather than paying all of it out. Anything not paid out to shareholders is recorded on their accounting ledger as Retained Earnings (earnings not yet paid out) or Capital Profit Reserve (gains on the sale of long-term investments not yet paid out).

Here’s where things are often misunderstood.

When an LIC receives these cash inflows, they can hold it as cash or reinvest it. These two figures (Retained Earnings and Capital Profit Reserve) don’t say anything about what happens to the money after it was received, and it doesn’t actually link up with specific assets that the LIC holds for smoothing dividends. These are nothing more than numbers in an accounting ledger. To get funds for dividend smoothing, if their cash position falls short, they will have to sell assets.

It can be easy to miss what I just said, so I’ll say it one more time. The retained earnings figure and capital profit reserve figure do not actually indicate that they have funds readily available to draw on for dividend smoothing. Anything required beyond what they happen to have sitting in cash at the time would need to be made up from liquidating assets.

What about franking? When an LIC gets franking credits from their underlying holdings and when it pays income tax, franking credits are gained, and when distributing franked dividends, they’re reduced. When returns are low, the LIC can then combine retained franking credits with cash (or selling down assets if cash is short) and smooth dividends. In a nutshell, the LIC is simply delaying the shareholders’ tax benefit.

When you read that an LIC has X years of dividend cover, it’s meaningless. The franking account balance is more indicative of the amount of dividends that an LIC could realistically pay out because there’s no benefit to distributing unfranked dividends.

As you can see, there is nothing special about dividend smoothing that you can’t do yourself.

However, there are some downsides to be aware of.

-

- If you went with open-ended funds such as ETFs and managed funds, you can hold safe assets such as cash or bonds yourself separately. The amount of cash or bonds you hold should be based on your risk tolerance, which is personal and individual, not what the average of all investors in an LIC needs. Why would a 25-year-old want the same amount of cash as a 65-year-old?

- With LIC’s, you don’t have access to the cash they hold when you need it, such as in a lay-off or other emergency.

- In an economic downturn, an LIC may liquidate risky assets which have fallen in price to maintain their dividend payout in order to satisfy their marketing of steady dividends, but when you do it yourself, you can live off the safe portion of your portfolio and leave your risky assets alone to recover when they’re priced low.

The worst thing about all of this is that it’s misleading. People see the marketing material and think the steady dividends are somehow safer than they really are.

LIC’s are a “Dividend Growth” strategy, so you’re ensuring your income will increase over time

Just because a company has a mandate to focus on dividend growth does not mean they will actually succeed.

Advocates of the ‘dividend growth strategy‘ use past data only from companies that survived and successfully increased dividends over a long period (decades) and leaves out the companies that did not survive. This is called survivorship bias. You cannot pick those companies ahead of time without knowing the future.

You can buy them at a discount to their underlying net asset value (NAV)

Another commonly cited point that tells only half the story.

The market prices companies. When they price an LIC at a discount, it is not just some wonderful free money — it has been priced lower by the market due to some risk. It could be manager risk, sector risk, risk of franking credit refunds disappearing, or a whole host of other reasons.

If the risk does not eventuate, you’re compensated with a higher return for taking that risk. If the risk does eventuate, you receive a lower return.

They have moved up the risk-reward spectrum.

It is a mistake to think there is a free lunch here. The market has priced it that way for a reason.

If you invest knowing there is a higher risk, that’s fine, but if someone fails to mention the downside, be careful when listening to them – they are telling you half-truths that could get you into trouble.

Summary

LICs made sense before index funds became available as they were a low-cost index proxy that was far and away better than the more actively managed funds. Today they offer little to no benefit over indexing, and even have risks that you can avoid by indexing.

In reality, while there are few legitimate reasons to hold LIC’s, I would expect their performance to be similar to that of the Australian index, so if you really want to, then go for LIC’s as the Australian portion of your investments — it’s most likely fine.

Final point

By far, the biggest problem with LIC advocates is that they promote it as a whole solution. As a result, it is framed in such a way that it seems like the investing decision is Australian LICs vs other Australian equities. You become so focused on deciding what type of Australian equities to invest in that it takes your attention away from the far more important concept of diversification of asset classes (both stocks and bonds) and diversifying throughout the other 45 investable countries.

As an example of this, let’s compare AFI to VDHG.

Diversification

VDHG invests in over 10,000 companies in 46 countries.

AFI invests in less than 100 companies, all in 1 country and 45% in just 10 companies.

Manager risk

VDHG is all index funds, so there is no manager risk.

AFI is actively managed, and it is easier to miss some of the few stocks that will make up most of the future returns, which would result in underperformance.

Better risk-adjusted return with multi-asset class portfolio

VDHG has a range of different asset classes, both high risk (emerging markets and small caps) and low risk (bonds), which when combined have shown to give a better risk-adjusted return, i.e. higher return for the same risk or lower risk for the same return — this is why diversification is called the only free lunch in investing.

DSSP

AFI has DSSP, which is one of the few benefits.

Whether that is worth the downsides is arguable. If I were on a high marginal tax rate, I’d rather just make up a portfolio of the underlying funds of VDHG (VGS, VGAD, VGE, VISM) and replace VAS with AFI if I wanted DSSP without sacrificing the other benefits of VDHG.

Provided you’re adequately diversified, using LIC’s for the Australian equities portion of your portfolio probably isn’t going to make much difference. If you use it as your sole investment, you have multiple unnecessary risks which could otherwise easily be avoided.