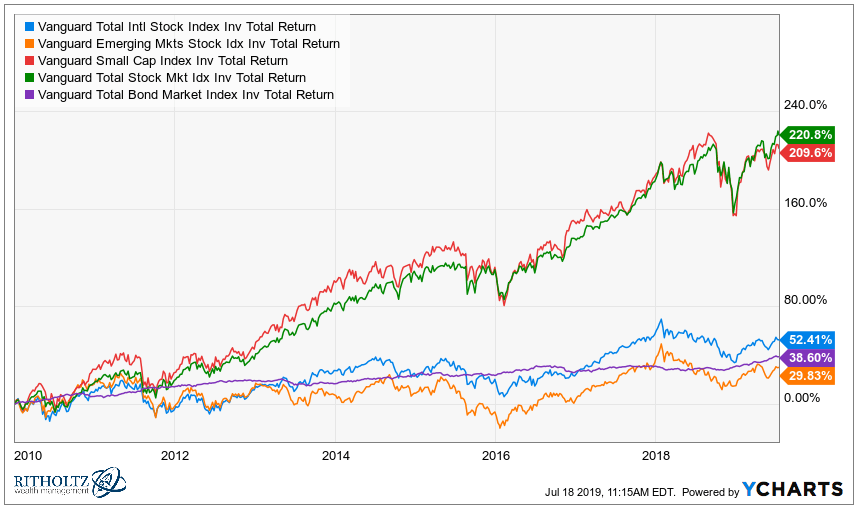

Emerging markets (EM) has done very poorly over this decade.

$10,000 in US stocks turned into $32,800

$10,000 in EM stocks turned into $12,983

We can blame this on a whole host of reasons, including political instability and corruption on a massive scale.

So, should we leave it out?

To answer this, let’s change the tense from

Emerging markets IS crap

to

Emerging markets HAS BEEN crap over a specific time period in the recent past.

Knowing of these returns over this time period would be useful if you could go back in time or if you could predict the future and know what will happen in the markets in the coming years.

The US has done extraordinarily well this past decade and outperformed the rest of the world.

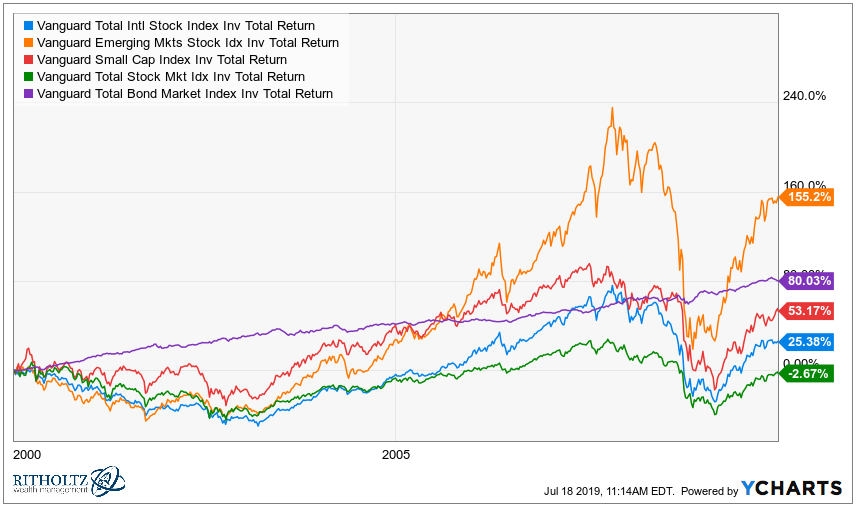

What if you used your same metric of looking at the past decade at the start of the last decade and only purchased the best performers in the decade to that point?

Looking at the image below, you would have kept non-US developed markets and emerging markets, thrown out all your US stocks, and missed out on the enormous gains in US stocks this decade.

Not only did emerging markets do better than the US, but they absolutely crushed them, and every other market – and this is despite the commonly cited argument that emerging markets are rubbish because of the corruption. Yes, there is a lot of corruption there, but even after accounting for this, they still outperformed.

Source: A Wealth Of Common Sense

Buying all markets is an explicit statement that you cannot predict the future performance of the markets.

Be wary of anyone telling you to over or underweight a market because what they are saying is that they can predict the future.

The case for emerging markets

While it is better to diversify between, say, 4 Australian banks than one, it is far better to diversify between companies in 4 different sectors (e.g. mining, IT, financials, utilities) than one because they each have a different source of risk. One is exposed to the risks within the IT market, another is exposed to a different set of risks in the financial market, yet another in mining, and so on. By diversifying your sources of risk, if a source of risk specific to that market shows up, the others will pick up the slack, and your overall return will be closer to your expected (or ‘average’) return than if you invested in just one sector.

This concept carries over to different markets. Emerging markets have different risks to developed markets, and as a result, they offer a diversification benefit.

I wouldn’t invest 50% of my money into emerging markets but having a portion in there offers a benefit.

The argument against this is that when there is a global crisis, all countries go down together, so there isn’t really a diversification benefit.

While this is true over short periods, over longer periods, different markets go up and down in a less correlated way that can be seen in the images above. It is during these longer stretches where diversification helps. You just need to avoid focusing narrowly on one part of the economic cycle to see it.

The case for emerging markets – a deep dive into risk premiums

Emerging markets have political instability — that’s kinda their thing. However, they’ve performed better historically precisely due to this higher risk, and this includes all of the corruption and other systemic problems.

It is known as a risk premium which is that people know all about these risks, and they price companies lower by way of not being willing to pay as much as for more stable companies to make sure that if the risk eventuates, they lose less, or more accurately, so that their “expected return” is higher to account for the higher risk. It is the same as with small companies, which are more likely to go under. The risk is priced-in. As a result of only being willing to pay less for those companies, the average returns over very long periods tend to be higher. Of course, this higher risk can mean higher highs and lower lows, and these can last for very long periods, such as the current decade, as shown in the image at the top of this article, so there’s no free lunch. You’re paying for these higher expected (or long-term average) returns with higher risk.

However, there is, in fact, a portfolio-wide free lunch when you include a small amount of these with the rest of your equities because they move up and down at different times, and this is why diversification is known as the only free lunch. In fact, I think emerging markets is one of the best diversifiers there is. It moves significantly out of sync to developed markets yet is a high-risk, high-return asset class just like developed markets.

It’s a mistake to think that people who invest in these higher risk asset classes, such as emerging markets and small companies, have no idea of the systemic problems in these asset classes and that somehow you know more than the rest of the market, which has priced these equities.