I had a reader ask:

I’d like to know why you avoid VISM (small caps)? Is it necessary to include VISM for total world exposure? Why are small caps considered risky?

There’s nothing wrong with small caps. I have some myself. The reasons why I haven’t discussed them on this site until now are:

- The goal of this website is to give the most valuable 5% of information that provides 95% of investing success.

- There’s conflicting research on the benefit of small caps.

- Any higher returns are not a free lunch — they come at the cost of higher risk.

Conflicting research

Initially, the research found that small caps provided higher returns, even when accounting for risk, which made them very lucrative because if this was true, you could replace large caps with a combination of small caps and enough bonds to dial down the risk back to that of large caps, and you have a higher return with no more risk! Who doesn’t like free money?

Unfortunately, that research was later re-done and with more data, and it was found that small cap growth companies dragged down a lot of the broader small cap market return. So there is no free lunch after all.

What is ‘growth’ when talking about ‘small cap growth companies’? Well, just as you can separate companies into small, mid, and large, you can also slice them into another dimension of value, blend, and growth.

Value companies are those that are valued low relative to tangible measurements such as earnings and book value. Generally, these are undervalued for a reason – either the industry or sector is suffering, the country itself is suffering economically, or it could be due to the company itself being poorly run. Growth companies, on the other hand, are those who appear to have a bright future. People see it and are willing to pay more than their fundamental tangible measurements such as earnings and book value in the belief they will grow and meet those expectations later (think tech companies as a current example). Small growth companies are sometimes called lottery companies in that they sometimes shoot the lights out and grow enormously (think 10 times or more), but most of the time, they don’t make it, and as a whole, they’ve been the worst performing segment. You can see why they are referred to as lottery companies!

Here is more information on small caps and their conflicting research.

The Problem With Small Cap Stocks – Ben Felix

Small Cap Blend vs Small Cap Value – Bogleheads.org

Telling Tales – 2017 update – Siamond – Bogleheads.org

Fresh Look at the “Larry Portfolio” from Portfolio Charts – Bogleheads.org

Why are small caps considered risky?

Large companies can afford to throw massive amounts of money at problems to overcome them. Small companies don’t have this ability. As a result, the smaller the company, the less likely they are to survive. We see successful large companies and are aware that they began as small companies, but often forget that the overwhelming majority of those small businesses failed or were taken over. Buyers of shares are aware of this, and as a result, they price-in the higher risk by way of not being willing to pay as much, thereby ensuring that if the company goes under, they lose less money on average. Not only to avoid losing more ‘on average’ when accounting for the higher number of failures, but even more to compensate for this higher risk (otherwise there would be no point in taking on higher risk by buying those shares if not for a higher return commensurate with it). More on risk premium here.

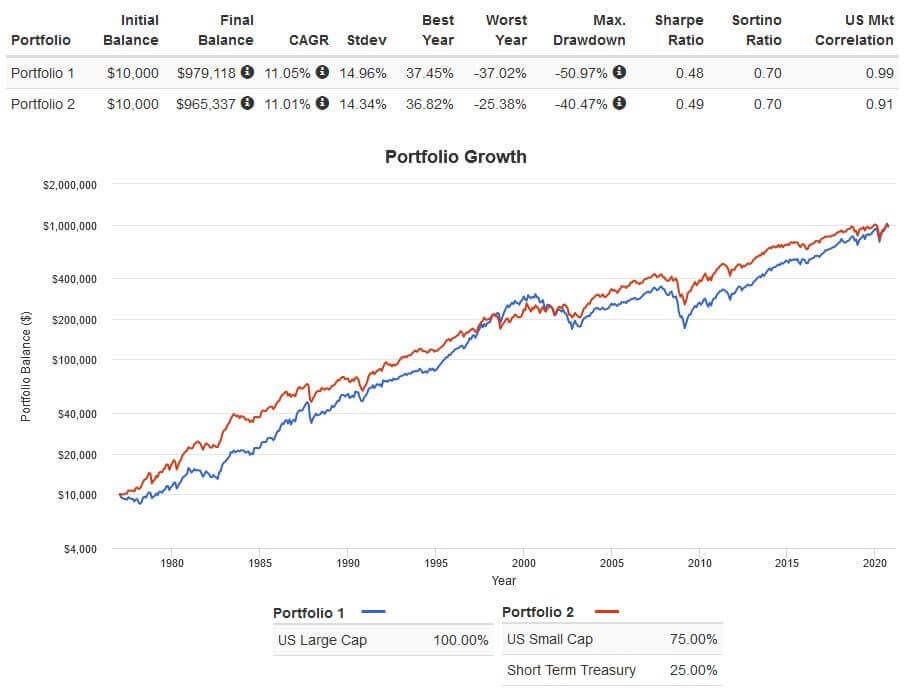

So, while the higher risk can be useful in that you get a higher expected return, that higher return comes at the cost of more risk. Below is a comparison of a 100% US large cap allocation compared to an allocation of 75% small caps and 25% short term treasuries. It shows that both the risk (stdev) and return (CAGR) are virtually identical, so there is no free lunch with small caps. You are simply increasing your risk, similar to just having a higher stock-to-bond ratio.

Having said that, once your equity allocation reaches 100%, adding small caps is one way to add further risk for an increased expected return without the added complications of adding leverage.

So, I can just leave them out?

Short answer – yes!

Due to the conflicting research and the likelihood that any outperformance is due to higher risk, which you can do by simply increasing your stock-to-bond percentage, I simplified the website to not talk too much about small caps, and instead focus on the concepts that are going to be far more important such as the risk-return spectrum, risk tolerance, diversification, and making a plan.

But you just said that you own it – what gives?

Yes, I do. I own small caps because large cap growth companies dominate the cap-weighted market by its nature of being cap-weighted. Yet large or small caps can individually underperform for long periods (a decade or more), which is why I think having some small caps can help with diversification during periods when large caps underperform.

However, I want to point out that at some point, the number of funds you hold is going to add complexity to managing your portfolio, and you have to draw the line somewhere. For instance, I think it would help diversification to replace some of the Australian index with a fund like Ex20 (which invests in the top 200 Australian companies minus the top 20 that comprise most of the index). You could also add some IHEB (emerging markets bonds), some DJRE (global REITs), some IFRA (global infrastructure), and you are up to managing 10 funds. You have to draw the line somewhere. The simplicity of Australian equities, global equities, and global equities (AUD-hedged) are the big three. Anything beyond that is a trade-off between benefit and complexity. I personally like emerging markets since it is far less correlated than small caps, providing (in my opinion) one of the best diversification benefits, but small caps, REITs, and a host of others could be used – or they could be left out, and you will still be getting the overwhelming majority of the benefit of investing in a globally diversified portfolio.

Conclusion

As you can see, there’s no ‘right’ thing to do regarding including or excluding small caps, and this is why I left it out of the website – why complicate education with something that is ambiguous and takes attention away from the big fundamental concepts like the risk-reward spectrum, risk tolerance, and making a plan, which in relative terms makes the decision to include a separate small cap fund barely relevant.

If I want to include it, how much should I use?

One way is to take the global equities and apportion it into cap-weighted proportions.

Let’s say you decided on 50/50 AUD/non-AUD for currency exposure, and 25% in Australian equities.

This would give you:

50% AUD

Australian equities 25%

Developed market equities AUD-hedged 25%

50% Non-AUD

Developed market equities LC/MC

Developed market equities SC

Emerging market equities

Cap-weighting is currently:

| Developed LC/MC | 76.5% |

| Developed SC | 13.5% |

| Emerging | 10% |

Which translates to the following in your 75% global allocation:

| Developed LC/MC | 76.5% | x 75% | = 57.5% |

| Developed SC | 13.5% | x 75% | = 10% |

| Emerging | 10% | x 75% | = 7.5% |

Which comes out to:

50% AUD

Australian equities 25%

Developed market equities AUD-hedged 25%

50% Non-AUD

Developed market equities LC/MC (57.5% – 25% =) 32.5%

Developed market equities SC 10%

Emerging market equities 7.5%

Using global allocation around cap weighting is what Vanguard appears to do with VDHG and their other diversified funds.

Another option is if you wanted to tilt towards small caps, you could always increase them. Just be aware that you are increasing the overall risk of your portfolio. Also, be aware that since large caps and small caps can underperform for long periods. If you have a substantial allocation of small caps, you need to be willing to hold them for a decade or more of possible underperformance. If you give up along the way, you would have done better by just leaving them out in the first place.

In reality, using 10% vs 15% isn’t going to have a material difference. What’s more important is having an allocation that you stick to relentlessly. An allocation should be like a marriage – something you commit to permanently.

What about using IJR (US S&P600 small caps, which is cheaper at ER of 0.07%)

IJR is cheaper, whereas VISM includes non-US small caps, and a larger proportion of US small caps, which IJR misses. The S&P600 is 600 hand-picked companies covering 3% of the US market by weight, whereas VISM has greater diversification even in the US with 1720 companies covering 14% of the US market and is a good match for VGS to get total US market coverage (as well as total non-US market coverage). VISM fits with a total market philosophy, but IJR seems to be a reasonable alternative given the lower fee.

If small caps growth drags down small caps, what about small cap value?

This makes sense in place of global small caps if we had that available on the ASX. The closest thing is VVLU, which is a global value fund. It does have quite a bit more mid and small caps than cap-weighting proportions, so it would be useful for the sake of diversification out of large growth companies that by definition dominate the cap-weighted index. An issue that concern me is that the funds under management are not growing, and I’m not entirely confident it will be available in the future. In fact, the most similar non-US fund to this is an almost identical fund on the London stock exchange, which was wound up in early 2021 even with $200m of assets under management. If not for this, it seems like an excellent way to diversify out of large cap growth stocks which dominate the cap-weighted index.

When overweighting small cap value stocks, just as with overweighting small caps or any other segment of the market, you have to be keenly aware of how hard it is to continue holding after a decade or more of underperformance, particularly as you see people left and right telling you why it will never do well again and abandoning it. Don’t discount the difficulty of this. This is another reason to think carefully before deciding to invest in VVLU.