With interest rates returning effectively nothing over inflation, is it worth moving cash into bonds?

To compare HISA (high interest savings account) and bonds, we need to compare the risk and return of each.

Risk

Bonds have interest rate risk — cash doesn’t

In investment terms, risk refers to the range of possible returns. The wider the range of possible outcomes, the higher the risk. No matter which way interest rates go, cash still has the same value, so there’s no interest rate risk with cash. On the other hand, the bond price moves in the opposite direction to interest rates, so bonds have more risk than cash since their value can change. As a result, to invest in bonds, we need to get rewarded for taking on the added risk. Otherwise, it doesn’t make sense to use bonds over cash.

The amount of risk we face depends on two aspects of bonds — credit risk and the duration of the bonds.

Corporate bonds come with credit risk — the risk that the company defaults and you lose not only future interest but also the principal. You can remove the chance of losing all your capital by diversifying, but during certain parts of the economic cycle, when businesses are under stress, your return will be lower than the yield of the bond fund due to losses from defaults. You can avoid credit risk by using only government bonds.

Government bonds (of developed countries) don’t have credit risk, which leaves just interest rate risk. The amount of risk depends on the duration of the bonds. As a rough guide, for each percentage of interest rate movement, the value of your bonds will move in the other direction by the bond’s duration. For example, if interest rates went up 1%, then 10-year government bonds would go down approximately 10%. We have no long-term (10-year plus) or short-term (sub 5-year) government bond funds on the Australian stock exchange, only intermediate-term bond funds with around 6 years effective duration. So if we look at a bond “crash” being a rise of 2% in interest rates in a short period, such as what happened in 1994, that would equate to a 12% loss in value. The other side of the coin is that when interest rates drop 2%, our bond funds rise by approximately 12%. So for government bonds, you can reasonably expect that level of risk at the extreme end. Compared with a potential 50% drop in equities in an economic crisis, you can see the risk in more perspective. There is certainly more risk than cash, but it isn’t in the same league as equities.

Returns

Past returns of bonds are a flawed and meaningless measure

Recent returns for bonds are in no way indicative of future expected returns, and if you assume so, it will almost certainly lead to decisions based on a misunderstanding of what you’re invested in.

The reason returns have been higher over the past few years is due to interest rates falling. Anyone who bought their bonds before the fall in rates could just as easily have faced rates rising instead of falling, resulting in the actual return falling below their expected return instead of what actually happened where the return went above the expected return.

For instance, last year, rates fell 3 times (a total of a 0.75% fall), and consequently, bond value increased 3 times. However, this can’t happen every year because we’re now at 0.75%, so there isn’t much further that interest rates can fall. It certainly can fall to zero and even below, but it just can’t really fall a lot more, so what happened last year could potentially happen again but not every year, and this is why you cannot go by historical returns.

Interest rates went crazy in the 1970’s all the way up to 17%, and over the last 40 years, it has come down from 17% to under 1%, so there has been higher than historical returns for bonds during these 40 years. At some point, the rates just can’t drop much more, and at under 1% interest rates, we’re around there. It could hit bottom now or in 1 year or 5 years, but there just isn’t much room for it to fall to get the same kind of return it has had in the past. For this reason, historical returns are just not a useful measure of expected return.

So what can we use to get a more accurate measure of what to expect?

Yield To Maturity (YTM)

With high-grade bonds such as those issued from the government of developed countries (VGB, for example), YTM is a very accurate measure of the expected return, where the expected return is like a weighted average of all possible or likely returns. At the time of writing, for VGB, it’s 1.3%

With aggregate bonds (meaning a mix of government and corporate bonds), there will be a risk of some defaults in the corporate bonds, so the expected return will be lower than the YTM, but for high-quality bonds, the YTM is the number you should be looking at for your expected return.

Now, interest rates can go up, which will have a loss in bond price.

Conversely, rates can go down, which will have gains in bond price.

You don’t know which way it will go, so your expected return remains at 1.3% currently (in the case of VGB), with your range of possible outcomes (risk) being wider than a HISA because no matter which way interest rates go, the cash in a HISA does not change and therefore has no interest rate risk. If you’re taking on more risk, you should be getting a higher expected return.

Normally bonds return higher than the short term cash rate, so in that case, bonds may be worth considering, but currently, the yield curve (the difference in added returns as you extend out the bond duration and therefore risk) is flatter than usual, which translates to very little gain with bonds over a HISA (if any, especially when you take into account the higher retail rates of HISA compared to wholesale rates such as with AAA).

So I’m not seeing an advantage of using bonds if you have a 3-5 year investment horizon at current rates.

When do bonds make sense?

The place where bonds make more sense would be:

- When you have a long time horizon to recover from the ups and downs and can just leave it in bonds indefinitely and drawing down gradually as needed, such as in retirement.

- If the yield curve was not so unusually flat so that you’re at least compensated for the risk.

- One reason I’d choose bonds over HISA now (if investing for the long term), even with such a flat yield curve instead of switching to bonds later, is that you just don’t know when bonds will go up or down or how much they will move. So I would avoid trying to time the market and just leave it in bonds in this case and get on with life.

- Another reason to use high-quality bonds over cash when investing for the long term is that bonds often (not always, but often) tend to go up when stocks are falling. This is because, in an economic downturn, governments often lower interest rates to stimulate the economy, and lower interest rates drive up bond prices. On top of this, there’s often a flight to safety in an economic crisis as people sell equities and buy government bonds. Both of these drive up bond prices offsetting losses in equities that you don’t get with cash. For this reason, with a longer time horizon, bonds are usually a better addition to stocks than cash is.

Conclusion

If you’ll be needing the funds within the next 3-5 years, when choosing between a HISA and a high-quality bond fund like VAF/VGB, I’d stick with the HISA. The risk (however small) isn’t providing a benefit at this time, yet you still get the downside of more risk. Even though bonds are much safer than equities, they’re a long term investment.

What if my time frame is long term and not 3-5 years?

In that case, cash may not have been suitable for you in the first place.

In the long term, the interest from cash tends to run close to inflation. If you live off the interest instead of reinvesting it, you’re eating away at the purchasing power of your capital even if the number of dollars remains the same.

If you’re in your senior years and have more than enough money to last the rest of your life, this may not be a problem, but this is a problem for the rest of us.

The lowest risk way of increasing your return while keeping your risk moderate would be a small amount of globally diversified equities mixed with bonds. For example, VDCO is an all-in-one fund by Vanguard that has 30% in globally diversified equities and 70% in bonds. If we consider an extreme stock market crash resulting in a 50% decline in your equities, your investment would go down by roughly 15% in total (50% of the 30% in equities). By facing this volatility, your expected return goes up.

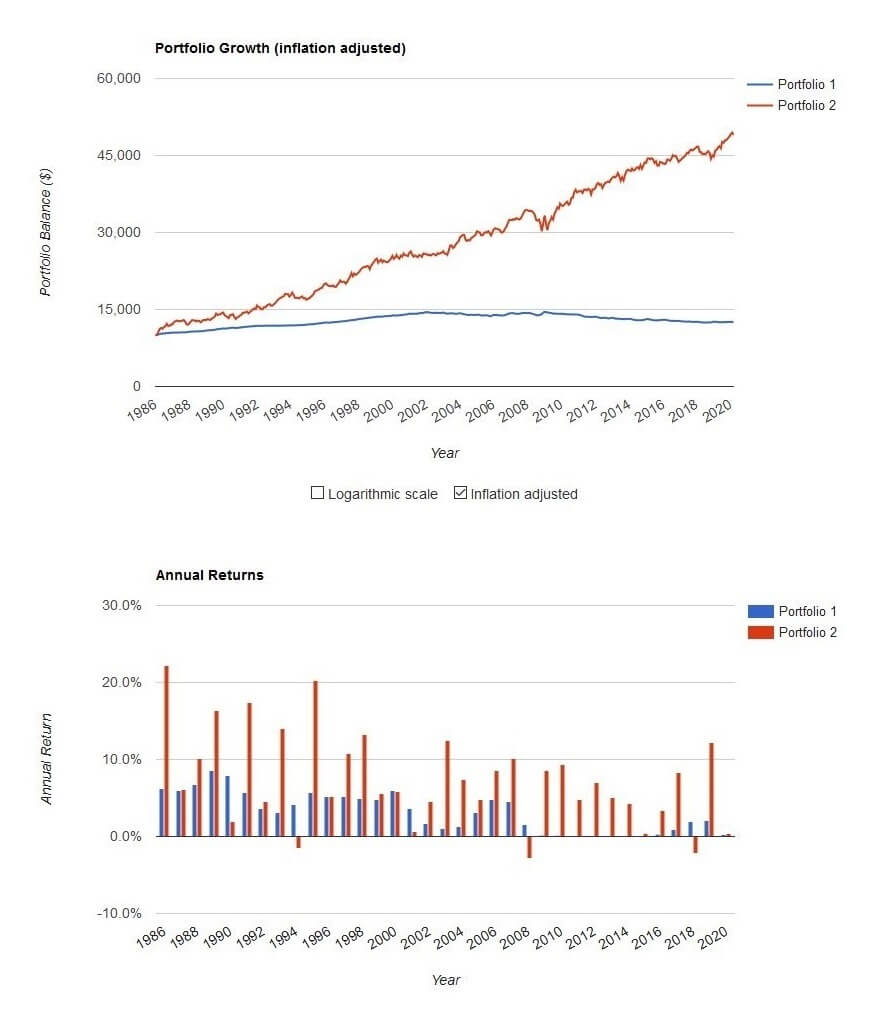

I don’t have Australian data, but going by US data, with a globally diversified portfolio of 30% stocks and 70% intermediate-term bonds compared to 100% in cash, the difference over the long term is significant. Below you can see that using the longest period available on Portfolio Visualiser being the past 34 years. There was a maximum fall of just 11.37% and a return of 7.44% annually vs 3.24% annually for cash. Looking at the image below with the inflation-adjusted box checked, you can see that when adjusting for inflation, the cash returned essentially nothing (as expected), so inflation was around 3%, meaning the return of the 70/30 portfolio vs cash was an annual 4% above inflation vs nothing above inflation.

It’s possible – likely even – that returns going forward will be lower due to the fact that interest rates fell during the past 40 years from a massive peak of around 17%, but adding risk is the only way to increase returns, and there’s no reason you need to go crazy and use a large amount of equities if your risk tolerance is low and your earning capacity and saving capacity can meet most of your needs.

What about a hybrid approach?

No, I don’t mean using hybrid securities. I mean mixing the idea of using something like VDCO to boost risk and return, but for shorter-term investments when the date of use is unknown.

I recently read of an interesting idea, which was to increase your funds by the maximum amount of risk so that if the risk eventuates, the money you need is still available.

For example, let’s say you were thinking of purchasing a property in the next five years, but you weren’t sure when or if you will definitely do that, and let’s say you needed a $100,000 deposit. Assuming a maximum loss of 15% with VDCO, you could invest $118,000 (85% of 118k = 100k) for the sake of bumping up your expected return. Then, if the risk eventuates where equities crash by 50%, you still have enough for your deposit, but if it doesn’t or if you end up buying a house in 10 years instead of 5, you’re expected return is high enough to not only offset inflation but even grow. If you’re still saving and don’t have $118,000 yet, then you would turn that into the time it takes to re-earn that $18,000. If you were saving $20,000-a-year, then you would assess if it was acceptable to buy a year later in the case that the risk showed up. Conversely, if you were only able to save $5,000-a-year, you might find that level of risk unacceptable.

The important thing is to understand the risk you’re taking to get the reward and to make sure you’re mitigating it somehow so that you can still reach your goals if the risk eventuates, and if you can’t financially tolerate that level of risk, don’t take on that risk and instead keep it in a HISA.

Further reading

The risk-reward spectrum

Bond funds

Cash vs bonds in your portfolio