One of the most innovative new funds was released in 2024 – GHHF.

GHHF is a leveraged ETF with a similar asset allocation to DHHF (Betashares all-in-one all-growth ETF), but it differs from most leveraged ETFs in that it is moderately leveraged and with lower management fees, making it more appropriate for long-term passive investing. However, while it is appropriate for long-term passive investing, it is still further up on the risk-return spectrum than an unleveraged fund, so it is only suitable for those with a high risk tolerance.

Read on to learn more about how GHHF works, what it invests in, how much leverage it has, how it is rebalanced, how much it costs, and more.

Quick Links

What is GHHF?

How does GHHF work?

What does GHHF invest in?

How much leverage does GHHF have?

Volatility decay

How is GHHF rebalanced?

How much does GHHF cost?

Can you negatively gear GHHF?

Who is GHHF suitable for?

GHHF in an SMSF

Is GHHF safe?

GHHF alternatives

How is GHHF different to an investment property?

How is GHHF different to a margin loan?

How is GHHF different to NAB Equity Builder?

How is GHHF different from borrowing against your home loan?

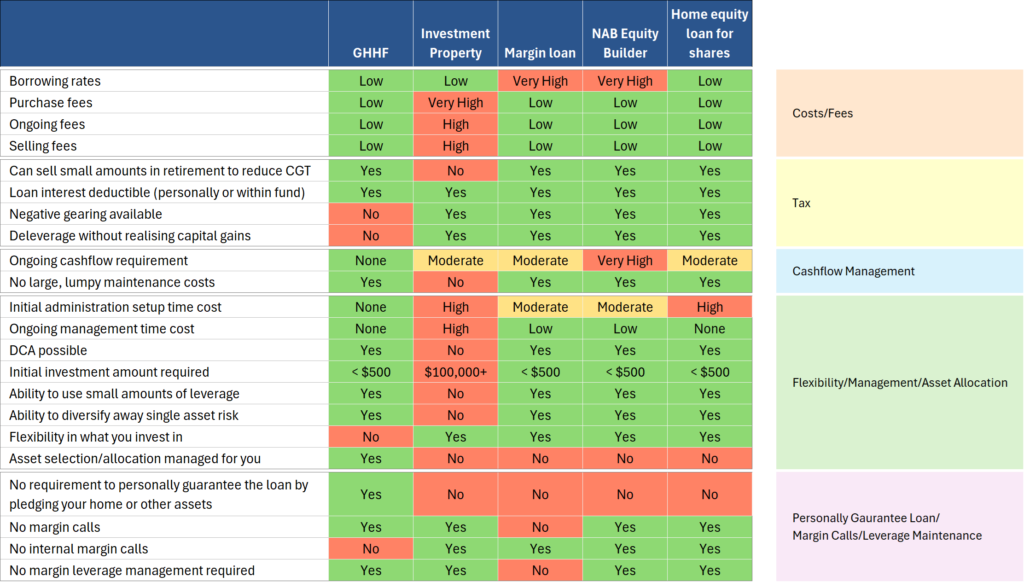

Summary Table of GHHF vs alternatives

GHHF Pros and Cons

Can GHHF be improved?

Final thoughts

What is GHHF?

GHHF is an internally geared fund (gearing is another name for leveraging), meaning that the investments it holds include the base investment plus internal borrowing that is used to purchase additional investments. This magnifies both the expected return and the level of market risk relative to a fund that is 100% shares.

Most geared funds are either rebalanced daily, have very high levels of gearing (200-300%), are confined to only Australian shares or only international shares, or have high fees that eat into your returns. All of this means they are not suited to long-term passive investing. In contrast, GHHF is only rebalanced when it hits predefined limits, has only moderate amounts of leverage, is an all-in-one fund with both Australian and international shares, and has a reasonable management fee, all of which is designed for long-term passive investing for those with a higher risk tolerance.

I have no affiliation with Betashares (or anyone else), but I’ve spoken to a Betashares founder a few times in the past with suggestions for passive investors. DHHF was the first, where they agreed to go with the first 100% growth diversified all-in-one ETF on the market for those not wanting the minimum 10% bonds in other all-in-one ETFs available, and I was pleased to see that come to the market. I noticed that Vanguard recently came out with an equivalent after seeing the success of this fund.

GHHF is the most recent, where I spoke to them and asked if they’ve ever considered a moderately geared version of DHHF for young accumulators with a high risk tolerance and long investment time horizon. The origin of that thought was that leveraging shares often means very high borrowing costs and margin calls, both of which are such significant downsides that most people simply don’t go down that route and, instead, usually go with investment property for gearing, which has a long list of its own downsides, which I will get into later in the article. A moderately leveraged all-in-one ETF overcomes many of these downsides and offers a great alternative.

How does GHHF work?

GHHF combines investors’ money with borrowed funds and invests the proceeds in a diversified range of 4 index-based ETFs for a leveraged version of a globally diversified 100% stock portfolio similar to DHHF.

GHHF has predefined minimum and maximum amounts of leverage, called ‘rebalancing bands’, where:

- If the investment falls in value to where the loan is above 40% of the total assets, rebalancing of the leverage occurs where some assets are sold to repay enough of the loan to bring the amount of leverage back within those limits, and

- If the investment rises in value to where the loan is below 30% of the total assets, rebalancing of the leverage occurs where more money is borrowed against the investment, and the proceeds are invested to bring the amount of leverage back within those limits.

This internal rebalancing does two things:

- Ensures the value does not go to zero in a market downturn, and

- Ensures that when someone purchases units of the fund, they will be buying in at a time with a known and expected amount of leverage.

These are the important questions to ask, which we will go through below:

- What does it invest in?

- How much leverage does it have?

- How is the amount of leverage rebalanced?

- What is the cost of the leverage?

- What is the cost of the investment management?

- Who is it suitable for?

- How does it compare to alternatives?

What does GHHF invest in?

GHHF is very similar to DHHF in its asset allocation in that it is an all-in-one high-growth fund continuing 100% index-based share ETFs.

GHHF’s underlying investments (their Strategic Asset Allocation) is:

| Asset class | Fund | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australian shares | (A200) | 37% | ||

| International shares | (BGBL+IEMG) | 44% | ||

| International shares currency-hedged | (HGBL) | 19% |

• International shares are a combination of a developed markets ETF (BGBL) and an emerging markets ETF (IEMG), which are maintained at market capitalisation ratio.

• International shares currency-hedged (HGBL) is developed markets only.

This provides the following characteristics in the underlying shares:

- 100% indexed equities

- Globally diversified across thousands of companies in dozens of countries, both developed countries and emerging markets

- 37:63 ratio of Australian shares to international shares

- 56:44 AUD-to-non-AUD based assets

This differs from DHHF, which does not use currency-hedged equities, and uses cap-weighted emerging markets in its entire international allocation, resulting in the only difference to the above points being the last point where it has the following, meaning it is exposed to more upside currency risk:

- 37:63 AUD-to-non-AUD based assets

How much leverage does GHHF have?

The most notable difference between GHHF and most other geared funds is that it is moderately leveraged.

GHHFs gearing ratio (the total amount borrowed and expressed as a percentage of the total assets of the fund, similar to a loan-to-value ratio, or LVR) will generally vary between 30% and 40%, which means you have between 1.43 – 1.67 times the unleveraged amount (called the ‘gross asset value’). I typically think of it as roughly 1.5x.

As a result, your daily returns will be about 1.5x that of a 100% stock portfolio with a similar asset allocation, less the cost of the interest, and the ups and downs will be about 1.5x that of a 100% stock portfolio.

This contrasts with most geared funds, which have 2-3x the gross asset value, which may be more aimed towards those looking for short-term active tactical tilts (i.e., market timing) as opposed to a long-term passive set-and-forget investment.

The paper Alpha Generation and Risk Smoothing Using Managed Volatility is worth checking out.

It does a good job of explaining the following:

- 1x (i.e., 100% growth assets without leverage) is technically ‘arbitrary’, and is not necessarily preferable compared to 1.1x, 1.2x, 1.3x, and so on

- There is an amount of leverage where the returns decrease, and a 3x leveraged fund produces a lower long-term return than a 2x leveraged fund

- Historically, as referenced by the paper, 1.5-2.0x leverage seems to be the sweet spot. This is seen on page 8 of the article.

The video also shows the higher risk (and much longer recovery period) of a 2x and 3x leveraged fund over a 1x (unleveraged) fund, allowing you to visually see how much longer it can take to recover the more leverage you have.

Thanks to Malifix on reddit for their assistance in pushing me to include the above, including the three numbered points, because, in their words:

“They may be useful for understanding the rationale behind gearing since there is a lot of weariness around leverage through US ETFs like TQQQ which have 3x leverage. I think many investors equate any leverage = bad. But do not appreciate why a ‘moderate’ leverage of 1.5x was chosen.”

Volatility decay

Volatility in the context of investing refers to the ups and downs of an investment.

Volatility decay is the phenomenon where the more extreme the ups and downs, the more there is a cost of that.

An example will clarify this.

Let’s say you start with $100.

If your investment goes up 5% and then down 5%, you end up with the following:

- 5% Gain = $100 x 105% = $105

- 5% Loss = $105 x 95% = $99.75

The reason for it not ending up back at $100 is that in the down phase, you are losing 5% of $105, not 5% of the original $100.

If we magnify the gain and loss to 10%, it becomes more extreme:

- 10% Gain – $100 x 110% = $110

- 10% Loss – $110 x 90% = $99

This loss is called volatility decay.

In any risky investment, there is volatility decay. This is because when an investment increases by 10% (to 110%) and then falls by 10% (from 110% to 99% since 10% of 110 is 99), there is a lower value than if the swings in returns were lower. The same result occurs if it falls in value by 10% first and then rises 10% afterwards.

You can improve this with diversification because not all the assets move up and down at the same time, and this reduces the level of volatility, but once you have diversified away unsystematic risk, you can’t escape this further. The higher your level of risk and return once you have removed unsystematic risk, the more volatility decay you will have.

Volatility decay is often mentioned as a downside of leveraged ETFs, where the rebalancing of buying high and selling low intuitively makes it seem like there would be more volatility decay eating away at returns than just the fact that the swings are more extreme, but SwaankyKoala from Reddit has been kind enough to share information on this showing that this is not the case.

Instead of the buying and selling causing additional losses compared to an unleveraged portfolio, there would instead be a different risk and return profile depending on the movement of the underlying investments. This is because leverage is added after the market has risen to its rebalancing band, so the growth would be more extreme as it rises to new heights after the rebalancing, and the losses would be more extreme as it falls until it is rebalanced. This means that returns differ when they come compared to the unleveraged equivalent, not that there is necessarily more volatility drag.

These links were provided by SwaankyKoala on reddit:

- Portfolio Rebalancing: Common Misconceptions (misconception 4)

- 2x vs. 3x LETFs : r/LETFs

This is an excellent article by SwaankyKoala on Geared funds: are they suitable for long-term holding?

How is GHHF rebalanced?

When I talk about rebalancing, I am not talking about rebalancing in the sense of rebalancing the underlying assets within the portfolio. I am referring to rebalancing the amount of leverage.

Let’s say you purchased at a time when the value of the share was $100 and the gearing ratio was 35%, meaning that for $100 worth of shares, there is an internal loan of $35.

Now, let’s say the shares rose by 20% to $120.

The gearing ratio has now become $35/$120 = 29%

As the 30% rebalancing band has been breached, the fund would borrow more money and purchase more shares with those borrowings to bring the gearing ratio back within its bands.

It does not say in the PDS how much it is reset to other than to be within the 30%-40% range. If we assume it is brought back to 30%, that would require 100%/70% x $85 = $121.43, which means borrowing an additional $1.43 per share and using that to purchase more stocks.

On the other hand, let’s say the shares fall by 20% to $80.

The gearing ratio has now become $35/$80 = 44%

As the 40% rebalancing band has been breached, the fund would sell down some shares to repay some of the loan to bring the gearing ratio back within its bands.

Again, it does not say in the PDS how much it is reset to other than to be within the 30%-40% range. If we assume it is brought back to 40%, that would require 100%/60% x $45 = $75, which means selling $5 worth of the underlying shares and paying the internal loan back for that amount.

What you may have realised by now is that the rebalancing band acts as a kind of internal margin call, where, instead of adding new cash into the investment to avoid it being sold by the company issuing the debt, it is deleveraged as a way to remain within a predefined amount of leverage. This mechanism stops your leveraged fund from going to zero in a market downturn and being irrecoverable.

How much does GHHF cost?

There are two important considerations when it comes to the cost of a leveraged fund:

- What is the cost of the leverage in GHHF

- What is the management fee of GHHF

What is the cost of the leverage in GHHF?

This is one of the most important considerations when deciding whether a leveraged investment makes financial sense.

At the time of writing, the RBA (Reserve Bank of Australia) has a cash rate of 4.1% and the Fed (The US Reserve Bank) has a cash rate of 4.33%. When I use the word “official cash rate”, I am referring to the cash rate set by the reserve bank, not the rate you get in your savings account.

Margin loan rates and NAB Equity Builder (NAB EB) are typically around 4-5% above the official cash rate

Home loans are typically around 2% above the official cash rate

GHHF loan rates are similar to what is listed on the Interactive Brokers page, which is about 1% over the official cash rate.

In the current lending environment of about 4% RBA cash rates, that translates to:

- Margin loan interest rates – 8-10%

- Home loan interest rates – 6%

- GHHF borrowing rates – 5%.

This is why margin loans are a significant hit to your expected returns.

If you expect shares to have a return of 10% (the historical average return), then in the current lending environment, you are looking at an expected return of the following after borrowing costs:

- 0-2% (i.e., 10%-8% to 10%-10%) with a margin loan or NAB EB loan.

- 4% (i.e., 10% – 6%) with a home loan

- 5% (i.e., 10% – 5%) with GHHF.

It is important to note that as you would be borrowing for the purpose of investing, the interest should be tax deductible. So, if your marginal tax rate is 32% (including the 2% Medicare levy), the borrowing cost beyond the income used for interest would be approximately a third less, and if your marginal tax rate is 47% (including the 2% Medicare levy), it would be approximately half, providing a significant boost to your returns. So, in the above bullet points, you can reduce the 8%, 6%, and 5% by your marginal tax rate.

It should also be noted that even though the gearing in GHHF is internally managed and tax is not deductible in your own name, it still has the same effect of being deductible since the internal borrowing costs are paid for from the distributions, and you only pay tax on the reduced distributions. The only difference would be with regard to negative gearing (explained in the next heading).

What is the management fee of GHHF?

The investment management fee (MER – management expense ratio) of GHHF is 0.35%, which is significantly lower than GEAR and GGUS at 0.80%.

Note that this investment management fee is also applied to the amount that has been borrowed since that is an additional investment. For instance, if the share price was $150, which represented $100 of base investments plus another $50 of investment from internally borrowed money, 0.35% is applied to the entire $150, called the Gross Asset Value.

This means that it is equivalent to a fee of 0.35% x 150/100 = 0.525% of the Net Asset Value

So, with the leverage being maintained within 30-40%, the fee based on the Net Asset Value can vary between 50% and 58.3% (0.35%/70% and 0.35%/60%).

The cost of the underlying investments it holds comes out of this, and on a leveraged basis.

0.35% is not much more than the 0.27% expense ratio of VDHG despite the additional work involved in running a geared fund.

Can you negatively gear GHHF?

What is negative gearing

Negative gearing is where borrowing costs for an investment (typically loan interest) exceed the income produced by that investment so there is an income loss in the financial year. Under Australian tax law, this can offset your personal taxable income.

For instance, if you borrow $100,000 with interest of $6,000 and income from the investment of $3,000, the remaining $3,000 income loss comes off your personal taxable income, and you get a tax deduction for that amount. If your marginal tax rate is 32% (including the 2% Medicare levy), then the government will effectively pay you about $1,000 of that $3,000 income loss via tax savings. For those on the 47% Marginal tax rate (including Medicare levy), you effectively get about $1,500 more via tax savings.

While making a loss of $1 to save $32c or $47c doesn’t make sense on its own, provided you have a globally diversified share portfolio, your total return (combined capital growth and income) is likely to be similar, so a higher-growth/lower-income investment would result in a similar total return, but when combined with negative gearing, you now have a higher after-tax return due to the tax deductions of negative gearing.

This additional return on your investment (for no additional investment risk) is obviously a very significant benefit. The downside to that is that you must be able to support the ongoing negative cashflow from other sources.

Can you negatively gear GHHF?

If we look at the yield of DHHF as an example and multiply it by 1.5x due to GHHF being leveraged by approximately 50%, we get 2.2% x 1.5 = 3.3%.

If we look at the borrowing cost of GHHF, since it borrows approximately 50% of the Gross Asset Value, it is approximately 5% x 1/2 = 2.5% at the time of writing.

If these figures are correct, it would be expected that GHHF is positively geared to around 1% p.a., which looks to be the yield showing at the time of writing.

This low distribution is a benefit to investors in that most of the returns are capital gains rather than income, and capital gains have the following benefits over income:

- Capital gains get the 50% CGT discount, whereas dividends/distributions don’t

- With capital gains, you’re able to earn money on unpaid tax that is delayed by potentially decades, unlike with dividends/distributions

- Capital gains are taxed only when you sell, so you can elect to delay realising capital gains until you are retired and you have no salary, paying low or no tax on the capital gain. In contrast, distributions are taxed while you’re receiving your full-time salary – and at your highest tax bracket, potentially even pushing you into a higher bracket.

However, if it was negatively geared, meaning that the borrowing cost was higher than the yield, investors in the ETF could not negatively gear it because an ETF is a trust structure and under the definition of the law, a trust cannot distribute losses. It must be carried forward to be used in future income years.

Who is GHHF suitable for?

GHHF is suited to those who:

- Prefer an all-in-one fund over the individual components

- Are happy with the asset allocation mentioned, and in particular, the relatively high allocation to Australian shares

- Have a very high risk tolerance, which is what the rest of this section is about.

The main consideration of GHHF is that it is leveraged

Conservative and balanced funds (funds with a large proportion of assets in low-risk/low-return defensive assets) are suitable for those with a low risk tolerance, such as retirees who have exceeded their retirement funding goals and have no need to take much investment risk.

High growth funds (funds with most or all of the assets in shares) are suited to those with a high risk tolerance, which is typically younger people with a long wealth accumulation phase ahead.

GHHF is an exaggerated version of a high growth fund as it has more than 100% in growth assets, which are acquired through the fund borrowing money to purchase additional underlying assets. So it goes to say that GHHF would be suited to those with a very high risk tolerance.

Risk tolerance has three aspects:

- Ability to take risk – If I take this amount of risk and things go badly, is there enough time and income to still reach my financial goal before I need the money?

- Willingness to take risk – Am I able to remain composed with this investment in a major downturn, or will I panic-sell at a low point?

- Need to take risk – How much risk do I need to take to reach my goal?

If a person does not have a long investment time horizon until they need the money, they do not have the risk tolerance for that investment. Due to the magnified level of volatility, this product is not suitable for anyone without at least 10 years until they need to access it, and if it is only 10 years, that should be when you expect to begin drawing down small amounts. If planning to redeem the full amount, a longer time horizon is needed to come anywhere near the long-term expected return.

Here is a great example of why.

During the GFC, the ASX took about 6 years to recover (when including dividends reinvested). In contrast, here’s a geared fund where the inception date was right before the GFC. From eyeballing the graph, it looks like it took 10 years to recover and has not caught up to its benchmark (the index) after 18 years.

If someone pulled their money out of that geared fund after a year, they would have lost a whopping 80% of their investment. If they pulled their money out after three years, they would have lost half. If they waited 10 years, they would have gotten their initial investment, which would have been a loss in terms of purchasing power due to inflation.

However, this would have been very different for someone holding a geared fund for long-term wealth accumulation, investing money into it regularly. This is because they would have continued to add to their investment for all those years while it was very cheap, so when the market finally did recover, the money they put in while stock prices were suppressed would have grown by a pronounced amount.

This is the great benefit of a long-term geared fund for accumulators with a long investment time horizon until they need it. They can continue accumulating steadily, and if there is a downturn, they benefit from continuing their regular investment additions at a low cost throughout the downturn. But they need to have the time to let it work.

They also need to be able to not panic-sell and instead hold on until the recovery, or the same thing would happen as above, selling it while it is down, resulting in a permanent loss.

And finally, there is the question of whether one has a need for such a high level of risk. If you can achieve your retirement goals without this much risk, why add additional risk without a need?

Once it is determined that someone has the risk tolerance to add leverage to their investments, the question is whether to use GHHF, an investment property, a margin loan, NAB Equity Builder, or borrowing against home equity. Borrowing against home equity offers the best range of advantages, but for those without equity in a property, until this fund came out, it was almost exclusively investment property, and GHHF’s real innovation is that it offers a fantastic alternative to consider, which we will go through below.

GHHF in an SMSF

GHHF in an SMSF is a very interesting use case for several reasons.

To protect your super, borrowing within a super fund must be a limited recourse borrowing arrangement (LRBA), which means that in the case of a default, the lender does not have recourse to get other assets within the super fund. This makes leveraging in super challenging. Very few lenders will take on the risk of lending within super, the LVR is lower, and the lending rates are higher. All of these reduce the ability to leverage as well as significantly reduce the advantages of borrowing.

At the same time, as super can not be accessed for decades, it makes it the ideal part of your assets to add leverage. In addition, using individually taxed superannuation structures, like an SMSF allows selling down in retirement and having the capital gains from all those years wiped and never needing to be paid.

GHHF solves the challenges of leveraging in super in several ways.

- As GHHF is internally managed and an ETF structure, it is non-recourse to the borrower, enabling it to be held within super

- Borrowing rates in GHHF are very low, unlike other forms of lending within super, where borrowing rates are higher as a result of the additional risk to the lender as a result of being an LRBA loan

- There is no credit assessment required to invest in GHHF like there is with other loans

- There are no ongoing cashflow requirements with GHHF like there are with other loans

- The high-growth/low-yield nature of GHHF, along with the ability to have CGT during accumulation effectively wiped when moved to an account-based pension in individually taxed structures, makes GHHF in an individually taxed superannuation structure one of the most tax-effective investments that exist

- The requirement to realise capital gains to deleverage GHHF in retirement is no longer a disadvantage due to having capital gains effectively wiped once it is moved to an account-based pension

- Leverage being suitable for long-term investing makes it a particularly attractive investment within super, which cannot be touched until preservation age.

The downside of an SMSF, of course, is that there are higher fixed costs for administration of the fund, so these make an SMSF not cost-effective for low balances. For instance, with a low-cost SMSF provider, you are going to pay a minimum of $1,300 p.a., plus the investment fee, so for a balance of $50,000, that’s 3% of your returns, which is likely to be all of your additional expected returns from leveraging, so you end up with more risk with your investment for no more gain. Additionally, there is more complexity around SMSF administration, management, legal requirements, oversight, and personal legal responsibility.

For more information on GHHF in an SMSF, have a read of SMSF Strategy: Geared Funds.

Is GHHF safe?

We have discussed market risk above, and there is a lot of market risk in geared funds due to the way leverage increases both market risk as well as losses and gains. This is the primary decision of whether to use GHHF.

As far as issuer safety goes, it should have the same level of safety as any other Betashares product, which is one of the largest ETF issuers on the Australian market with over $50 billion in funds under management. They have an Australia Financial Services License through ASIC (the regulator), which requires the assets to be held in trust for the benefit of investors and held separately from the assets of the Betashares. The assets within the ETF units are held by third party custodian Citigroup Pty Ltd, which cannot legally be used by Betashares.

These ETF units can then be purchased through a CHESS-sponsored broker, which means the ETF units are held directly in your own name, or they can be held by a custodian-based broker that holds legal title for you as beneficiary.

GHHF alternatives

Alternatives to GHHF for leveraging include:

- Investment property

- Margin loans

- NAB Equity Builder

- Borrowing against home equity

How is GHHF different to an investment property?

As I mentioned earlier, when people want to leverage to move up the risk/return scale beyond 100% growth assets, property is the go-to due to the ease of getting large amounts of leverage, low borrowing costs, and no margin calls. However, leveraging with an investment property has several major downsides, including:

- Inability to invest small or moderate amounts

- Inability to invest in an ongoing, consistent manner (known as ‘dollar cost averaging’ or DCA)

- Inability to use a small amount of leverage (it’s usually 400% leverage, which is a lot of risk)

- A massive amount of single-asset risk

- Very high purchase fees that eat into returns

- Very high ongoing fees that eat into returns

- Very high selling fees that eat into returns

- A lot of work to purchase and for ongoing management

- Large lumpy costs when unexpected maintenance is required

- Inability to sell small amounts in retirement to reduce CGT payable.

GHHF offers an excellent alternative that solves a lot of these issues with the following:

- Ability to invest small amounts

- Ability to consistently buy small amounts as part of a regular investment plan

- Ability to use a moderate amount of leverage

- Broadly diversified without single-asset risk or single-market risk

- No purchase costs (free brokerage is now available on several platforms)

- No selling costs

- Very low ongoing costs

- No ongoing management required

- Ability to sell small amounts in retirement to reduce CGT payable.

Investment property does have some advantages, though, namely:

- The ability to negatively gear

- The ability to take on an extremely large amount of leverage (if that is what you are looking for)

- No internal margin calls, so provided you are able to make the mortgage repayments, you’re unlikely to sell at a low point

- You can deleverage by paying it off without requiring selling and realising capital gains to deleverage.

In terms of borrowing cost, GHHF has leverage that is at least as cheap as a home loan, if not cheaper.

How is GHHF different to a margin loan?

A margin loan is a loan that lets you borrow money to invest in more shares. You typically use your existing shares as collateral for the loan. A key aspect of a margin loan is a ‘margin call’, where, if the market value of your shares drops to where your borrowed amount is above a certain percentage of your total investments (combination of shares put up as collateral plus the shares bought with the borrowed funds), you get a call to reduce your leverage, or they will do that for you. You have the option to use cash or sell shares to reduce the loan. This requires careful management of your margin loan to reduce risk.

Note also that margin loans require undergoing credit checks which involves significant administrative burden and paperwork. Typical margin loans will also require the borrower to put up additional security as collateral beyond the value of the assets they are lending against

The risk mitigation needed, administrative burden, and high interest rates make margin loans unpopular.

Like a margin loan, GHHF:

- Uses leverage to increase returns (and risk)

- Decreases leverage when the market falls far enough, so this works internally like a margin call.

Unlike a margin loan, GHHF:

- Is less flexible

- The amount of leverage is determined by Betashares, which you cannot control

- What you invest in is determined by Betashares, which you cannot control

- Leverage is managed internally for you

- To maintain leverage, not only is the leverage decreased when the market falls, but leverage increased as the market rises

- Has higher investment management fees

- Has much cheaper borrowing rates

- Requires no credit checks or administration to open beyond that of buying an ASX-listed security

- Does not require additional security and personal guarantees as collateral

- Has no ability to negatively gear

- Requires selling and realising capital gains to deleverage

The big points are that it is less flexible, you cannot negatively gear, and you are required to realise capital gains to deleverage. However, the borrowing costs are much cheaper, impacting the returns in a significant way, and leverage is managed for you.

How is GHHF different to NAB Equity Builder?

NAB Equity Builder is a unique product that allows you to borrow against existing shares to invest in more shares and ETFs, similar to a margin loan, but without margin calls. The catch is that you must make Principal and Interest (P&I) repayments, and it is over a short loan term of 15 years, meaning the repayments are very high.

Like NAB Equity Builder, GHHF:

- Uses leverage to increase returns (and risk)

- Borrows against existing shares

Unlike NAB Equity Builder, GHHF:

- Is less flexible

- The amount of leverage is determined by Betashares, which you cannot control

- What you invest in is determined by Betashares, which you cannot control

- Leverage is managed internally for you

- To maintain leverage, not only is the leverage decreased when the market falls, but leverage is increased as the market rises. In contrast, with NAB EB, provided you can continue making your loan repayments, there is no requirement to sell when the market falls

- Has higher investment management fees

- Has much cheaper borrowing rates

- Requires no credit checks or administration to open beyond that of buying an ASX-listed security

- Has no ability to negatively gear

- Does not require the very high repayments required when using NAB Equity Builder (or any repayments)

- Requires selling and realising capital gains to deleverage

The big points are that it is less flexible and you are required to realise capital gains to deleverage, but also that the borrowing costs are much cheaper, impacting the returns in a significant way, and NAB EB requires P&I repayments for leverage over 30% LVR and the loan term is only 15 years (10 years if LVR is over 70%). This means the repayments are extremely high, which you have to pay from your personal cashflow, limiting the amount most people can afford to borrow.

How is GHHF different from borrowing against your home loan?

Borrowing against your home equity is the ideal scenario for leveraging. You get low borrowing rates, have full flexibility to invest in anything you like, no margin calls (you just need to keep making the repayments), can get 30-year repayments with the option for interest-only (IO) repayments to lower repayments and the hit to your cashflow even further and can deleverage without realising capital gains.

GHHF is a leveraging option to be considered for those who cannot borrow against equity in their home. For instance, those who have not purchased a home yet, or who have not built up enough equity to borrow from it yet.

Like borrowing from your home to invest, GHHF:

- Uses leverage to increase returns (and risk)

Unlike borrowing from your home to invest, GHHF:

- Does not require any additional security (like your house) to be put up as collateral against losses

- Is less flexible

- The amount of leverage is determined by Betashares, which you cannot control

- What you invest in is determined by Betashares, which you cannot control

- Leverage is managed internally for you

- To maintain leverage, not only is the leverage decreased when the market falls, but leverage is increased as the market rises. In contrast, when you borrow against your home loan, provided you can continue making your loan repayments, there is no requirement to sell when the market falls

- Has higher investment management fees

- Has slightly cheaper borrowing rates

- Has no ability to negatively gear

- Requires selling and realising capital gains to deleverage.

The big points are that it is less flexible, and you are required to realise capital gains to deleverage, and while borrowing costs are cheaper, they aren’t as much of an impact as compared to margin loans. However, it requires a home to borrow against and to be collateral, which adds risk.

Summary Table of GHHF vs alternatives

GHHF Pros and Cons

Pros

- Easy to understand

- All-in-one fund managed for you

- Diversified globally across thousands of assets in dozens of countries

- Very low internal borrowing costs

- Relatively low-cost

- Index-based investments

- No margin calls

- No credit checks

- No personal guarantees

- No admin to open

- Leverage management is done for you

- Liquid

Cons

- Less flexible (cannot choose your asset allocation or the amount of gearing)

- Higher investment risk

- Higher investment fees

- Cannot deleverage without realising capital gains

Can GHHF be improved?

If it were up to me, I would make some changes:

- A lower Australian shares component – The Australian stock market is very concentrated in two sectors, which adds a lot of concentration risk.

- Emerging markets would take into account HGBL. It is currently market weight with BGBL, but since HGBL invests in the same international stocks, it means emerging markets are underweight to their 63% international allocation. At the time of writing, it appears that the actual amount of emerging markets is more accurate than the strategic asset allocation, so they may be accounting for this in the implementation, despite not using that in the strategic asset allocation.

- Small cap value – An ideal all-in-one fund would include some small cap value (SCV) funds, and that would also be the case for DHHF.

The above could be somewhat adjusted by mixing GHHF with a global SCV fund. While we currently have high-fee funds that could potentially fill that, they have high fees and do not specifically target small cap value (e.g., QSML). Avantis has created a fund in Europe that holds a combination of AVUV & AVDV for a fee of only 0.22%, and there have been some comments that they may come to Australia to offer the same thing, which would be a nice complement.

Final thoughts

GHHF is a high-risk, high-return investment that is only suitable for those with a high risk tolerance and a long investment time horizon.

Until now, investment property was the go-to investment for those with a high risk tolerance wanting leverage, but it comes with a long list of significant downsides. GHHF is an exceptional alternative without many of the downsides of investment property while also offering much lower borrowing costs than margin loans and NAB Equity Builder.

The high-growth/low-yield nature of GHHF, the requirement to realise capital gains to deleverage, being suitable for long-term investing, and being non-recourse to the borrower makes it a particularly attractive investment within super, which cannot be touched until preservation age, and where using an individually taxed structure allows selling down in retirement and having the capital gains from all those years wiped and never needing to be paid.

It’s great to see this option come to the market, and Betashares should be commended for their innovation in bringing it to the market at a reasonable cost.