Asset classes

An asset class is a group of investments that have similar financial characteristics.

The main passive investment asset classes are

- Cash – money in the bank.

- Bonds – essentially fixed-term deposits that can be bought and sold on the market.

- Equities – publicly held companies.

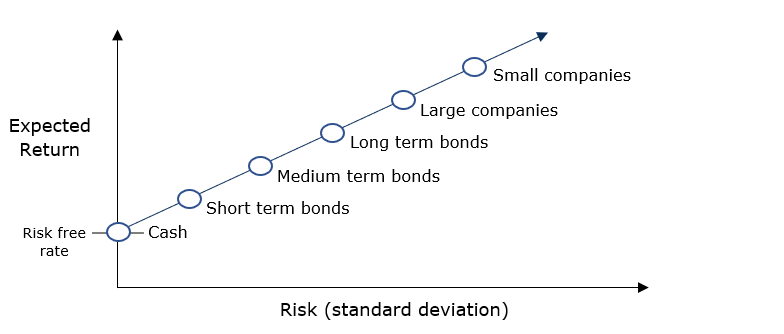

Each of these has a risk and a reward. The reward is the expected return. The higher the risk, the higher the expected return, but also the wider the range of possible returns.

Let’s go through the above asset classes and see what that means.

Cash

Provided your money is in a government-guaranteed institution, and under the insured amount, there is no risk. No matter what is happening in the market or with interest rates or economic conditions, you get your guaranteed principal back. Since there is no risk, you get no compensation by way of a higher reward, and you essentially get little-to-no ‘real’ (i.e. after-inflation) return.

Bonds

The next asset class up the risk-reward spectrum is bonds.

A fixed-term deposit is where you loan money to a bank and in return, they give you an IOU saying they owe you that amount of money – plus some agreed-upon interest amount each pre-determined period until maturity.

Bonds are essentially the same thing, but you can buy and sell these IOUs on the market. So, if you want out, someone else pays you out, and then that person gets the IOU and remaining interest payments until the bond matures or until they sell it to someone else.

So why do bonds have a higher risk than cash?

Because when interest rates go up, the value of the bond goes down and vice versa.

When interest rates go up, since the interest return on an existing bond is guaranteed at the previous lower rate to what is now available in the market, the bond goes down in value to compensate anyone who will buy it. Otherwise, they would go and purchase a newly issued bond instead.

For example, let’s say you had a 7-year duration bond and interest rates went up by 1%. Your principal would go down by 7% to compensate for the 1% interest lost each year for the remaining seven years.

Conversely, if interest rates go down, but you still have the previous higher guaranteed interest rate, the value of the bond will go up.

For taking this risk, you’re compensated with by a higher expected return.

Let’s stop here and see what expected return means.

Expected return

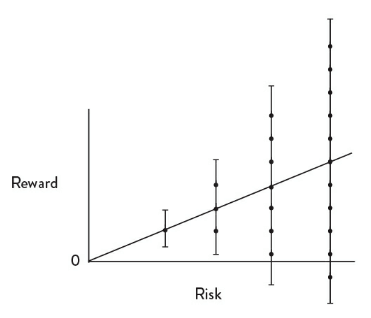

Brian Portnoy shared this graph in his book The Geometry of Wealth to show how the relationship between risk and reward tends to work.

The expected return is essentially the weighted average of all potential outcomes.

The higher the risk you take, the higher the expected return (the point on the diagonal line), but it also increases the range of potential outcomes. There’s no guarantee that your actual return will be your expected return. To get this higher expected return, you face the risk of any of the range of possible returns for the risk you’re taking.

Back to the asset classes

Historically bonds have provided a slightly higher return due to the slightly higher risk.

Bonds have two main risks that you have a choice over.

- Interest rate risk (based on the duration)

A 3-year bond has a lower risk than a 10-year bond, which in turn has a lower risk than a 25-year bond because when interest rates move, the range of possible outcomes increases as the term increases. For taking this risk, you get a higher expected return with longer duration bonds of the same credit quality. - Credit quality risk

If you loan money to unestablished companies, they have a higher chance of defaulting and you losing your money, so to compensate for this, you get a higher expected return.

Note however that while the expected return of a high-quality bond is the interest rate, the expected return of a low-quality bond is less than the interest rate since a percentage of the time the principal is lost due to defaults.

As we would be using bonds for safety and preservation of capital, we want to avoid credit risk and instead go with high-quality bonds.

Bonds are used when the funds are not earmarked for anything for the duration of the bond. This is because when interest rates go up and the resulting value of the bond goes down, if you will be holding the bonds until maturity, the drop in value is made up for by the increased interest you get each year for the duration of the bonds. This is not the case if you sell the bonds before the maturity date. For example, if you were planning on using the funds in 5 years, you would ideally get a 5-year bond. This way, you get a higher expected return for taking on duration risk. Since investors aren’t going to lock up their money for five years if the return is the same as a 1-year bond, to get people to buy it, the 5-year bond offers a higher return.

During different parts of the economic cycle, the returns of intermediate-term (5-10 year) bonds can come close to the returns of short-term term deposits, which is the case now. So at this time, choosing a fixed-term deposit instead, which offers no duration risk but a similar return makes sense. How long this will be the case can’t be known until it is in the past, but in the long term, cash is almost guaranteed to have lower returns since risk and return are inextricably linked.

By the way, you may be wondering why a 5-year term deposit, which technically is in cash, is not considered risky. After an interest rate increase, wouldn’t the value of the overall investment still be lower compared to someone who got a 5-year term deposit after interest rates increased due to being stuck with lower interest rate payments? Yes absolutely. So, just to confuse you, I consider anything over one year, whether in bonds or fixed-term deposit, to essentially be bonds and come with the higher associated interest rate risk. Similarly, I consider anything one year or less to essentially be cash, whether actually in bonds or cash and come with the lower associated risk.

The take-home point is to think in terms of risk-and-return of specific investments, not just the broader classification.

Even with the slightly higher return of bonds to reduce the eroding effects of inflation, you will be unlikely to get enough of a return to live off bonds alone for a decades-long retirement, which brings us to stocks.

Equities

Equities (or stocks) are businesses that are publicly listed on the stock market that you can buy and sell shares in.

These are a high-risk asset class and as such, have a high expected return. Along with the high expected return, the range of possible returns with equities is wide (although the range narrows the longer you hold them).

These are going to be the assets that produce the return we need to give us the highest chance of success to survive inflation and drawing down from our portfolio over decades.

This doesn’t mean we should use only equities, because we also have other requirements, but equities are the go-to asset class for increasing return.

Equities are not suitable for short-term investment

Due to the volatility of equities, they’re not suitable for short term investments of under about 5-7 years because the market may be down at the time you need it and withdrawing at that time will crystallise the loss, whereas the ability to leave it invested would allow it time to recover. Anything that you will need in that time should be in a risk-free investment such as a fixed-term deposit.

Let’s say you were saving to buy a house in the next few years and you invested that money into shares. If there was a market crash after three years that took another six years to recover (this is not at all unusual for the stock market), then by the time you need it, you will be selling at a loss and need to spend more time (potentially years) re-earning money. And during that time, the property market could boom and cost you hundreds of thousands more. Being strategic means deliberately missing out on things lower on your prioritised list of needs to focus on things higher. If home ownership is high on your short-to-medium term agenda, then you should be mindful of the effect of investing that money in high volatility assets may result in.

Asset sub-classes

Within each asset class, some sub-classes are further up or down the risk-return spectrum.

Within bonds, the longer the term and the lower the credit quality, the higher up on the risk-return spectrum.

Within stocks, small companies will be higher on the risk-return scale, as they are not yet established and are riskier.

Large companies are more well established and as such are lower on the risk-return spectrum than other stocks.

Final thoughts

You’ll need to take some risk, but at the same time, not too much risk.

To decide on an allocation that suits you, you would use a proportion of equities for growth and then decide on a proportion of a low-risk asset like bonds to dial up or down the overall portfolio risk to what suits your situation.

An allocation of stocks-to-bonds of 50/50 means half your money is in risky (or growth) assets, and half is in risk-free (or low risk) assets. If there is a market crash and equities drop by 50% as they did during the GFC, a 50/50 allocation would only drop 25% overall – the first 50 in equities halving and the second 50 in bonds preserved. The flip side is that during a bull market as we have had since then, you’ll only get around half the growth of a 100% equities portfolio.

If you want or need a higher expected return, it will come with higher risk. If anyone tells you that you can get a higher return without higher risk, they’re lying. By believing that there is some elusive little-known investment offering a higher reward without higher risk, you open yourself up to believing salespeople who are out to rip you off by tapping into your greed.

Further reading

Why I haven’t discussed other asset classes

Cash vs bonds in your portfolio