The “index” refers to the entire investable market where the allocation of each company is in proportion to its value.

So if Commonwealth Bank is valued at double BHP, it would be valued at double in the index and similarly for all companies.

An Australian index contains all the stocks in the Australian market in their valuation proportions.

An emerging market index contains all the investable stocks in the 23 emerging countries in their valuation proportions.

A developed countries index contains all the stocks in the 23 developed countries in their valuation proportions.

You get the idea.

Investing in an index allows you to say

I don’t know anything about choosing a company, sector, country, or anything else, and I also don’t know how to choose a fund manager capable of choosing them. I accept that I don’t know. But I still need to invest for my future.

Investing in an index fund allows you to invest in the entire market – without the risk of you or anyone else selecting the wrong stocks – by just buying everything.

Important points about index funds

1. Fees

Before index funds were available, if you had no idea how to pick stocks to invest in, your only option was to invest in actively managed funds.

They generally charged around 2% of your total assets invested with them each year for picking their stocks for you.

Let’s take a look at the numbers.

The long-term return for Australian and the US equities markets has been 6% above inflation.

2% in fees means you have lost a third of your return.

And compounding works both ways – the longer you compound gains, the more of a positive effect compounding has, but the longer you compound losses, the more of an effect compounding has on your returns, but in the other direction.

Let’s look at the effect after 40 years of compounding on a $100,000 investment.

The first with 2% management fees taken out. The second at 0.2% management fees of index funds taken out.

$100,000 for 40 years at 4% compounded annually = $480,102

$100,000 for 40 years at 5.8% compounded annually = $953,732

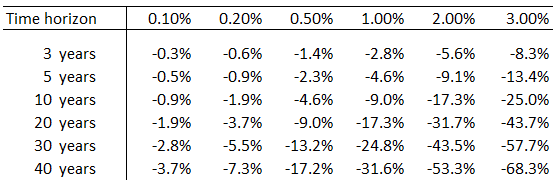

Those fees cost you half your net worth. When it comes to fund management fees, 2% is an enormous amount. Even 1% is nowhere near acceptable, as you can see in the chart below. At the 10 year mark, you can get an estimate of your costs by multiplying the expense ratio by ten, and it just gets worse after that.

In case it is still unintuitive, this article articulates how small-sounding 1% fees cost you a third of your nest egg.

2. Performance

With index funds, you’re guaranteed the performance of the entire index.

You might think that fund managers can pick better performing stocks so you can get a return that makes up for the fee and more, but the data is out on this. S&P has been tracking active management performance for a long time now and release regular SPIVA reports. Their findings are that while over any 1 or 2 year period, an active manager may outperform the index, over 15+ years, more than 80% of active managers fail even to match the index after fees.

This can be explained by the Pareto Principle (the 80/20 rule).

Most of the future performance will come from a disproportionately small number of companies in the market1,2, and it’s much easier to miss some of these few companies resulting in lower returns than just investing in everything. As a consequence, a disproportionately small number of fund managers outperform by a large magnitude, and a disproportionately large number of fund managers underperform. So when you pick a fund manager with no real idea where they will end up, you have a much higher chance (over 80% going by the SPIVA reports) of ending up with one that underperforms.

And while there are some actively managed funds that outperform, the probability of identifying them ahead of time is very low. Not many people knew in 1960 that Warren from Omaha, Nebraska, was going to deliver stunning returns, and he only became famous once most of his stunning returns had already been delivered.

1. The 15-Stock Diversification Myth

2. Do Stocks Outperform Treasury Bills? — “4% of listed companies explain the net gain for the entire US stock market since 1926“

3. Fund Manager Risk

Fund managers can and do make mistakes in their investment choices. Here is an article about a fund manager who the BBC once described as “The man who can’t stop making money”. He made unusually good returns for a long time and then messed up so badly, with billions of investors’ dollars in funds, that they had to “gate the fund” to stop investors from taking out their own money so as to avoid a fire sale (selling below value to pay out investors), causing massive losses to his investors.

The greatest benefit of indexing, which is never really discussed, is that it also removes agency risk — the risk that the management uses its authority to benefit itself at the expense of shareholders.

All investors in the market are made up of a combination of index investors and actively managed funds. The index investors are, by definition, getting the market return. So when we look at the average of all funds collectively under active management, the performance will also be that of the market (minus fees) – because if you could pick which managers will outperform, we would all pick those. When you go with active management, you get the same expected return as indexing, but you now have additional risk. Why take a risk without a reward?

For those who argue that you can outperform by picking an active manager, the problem is that since you can’t know in advance which funds will outperform and which will underperform, you’re not increasing your expected return. What you’re doing is increasing the range of possible outcomes (which is the definition of risk) without increasing the expected return, which is the definition of gambling.

Imagine a game of roulette. 1 in 37 times you get 37 times your original bet, and the other 36 times you get nothing, so your expected return is (37 x bet + 36 x 0)/37 = your original bet. Your expected return equals your original bet, but you’re hoping that it will land in the higher end of that larger range of outcomes, but hope is not an investment strategy. This is the difference between gambling and investing.

4. Diversification and avoiding idiosyncratic risk

Idiosyncratic risk is the risk of buying a single stock or a single sector of stocks, or a single country’s stocks.

Let’s say you expect a company to fail, on average, 5% of the time.

If you invest in 1 company, you have a 5% chance of a complete loss of capital.

If you invest in thousands of companies, there’s no chance that all companies will fail. Instead, you will get much closer to your expected return of a 5% loss of capital. Compensated by the profits of the other 95%, you wouldn’t even notice it.

What about blue chip companies – they’re too big to fail, they’ll always land on their feet.

Are you sure? What about Xerox? And Polaroid? Kodak? Nokia, Blackberry, Control Data, Nortel, Worldcom, Palm, Blockbuster, Burroughs, Reader’s Digest, Digital Equipment Corporation, Schlitz, Enron, General Motors, General Electric, …

So if we go back to the risk-reward spectrum in the previous article, we can see that with diversification, you’re getting the same expected return but with lower risk, i.e. a lower range of possible outcomes.

What this means is that diversification is a free lunch – an upside with no corresponding downside.

It goes the other way too – idiosyncratic risk, just like fund manager risk, is a risk without a reward – it’s a silly risk to take when you think about it.

When you invest in just one company, one sector, or one country, you’re taking an uncompensated risk.

The take-home message is to diversify broadly.

Index funds are the cheapest and most efficient way to diversify broadly to mitigate idiosyncratic risk.

5. Tax efficiency

In actively managed, the fund manager regularly rebalances (buys and sells) the securities in the fund based on what it believes will outperform in the future, and this changes regularly based on news coming out. This results in investors having to ‘realise’ capital gains (i.e., pay tax capital gains).

In an index, there is extremely little rebalancing because the proportions of a company’s weight in the index changes based on the company’s value changing, which is not based on any buying and selling. So your ‘unrealised’ capital gain can continue to earn returns for longer. The returns on unrealised capital gains can be viewed similarly to an interest-free loan from the government until the assets are sold, potentially decades away. This further improves the returns of passive investing over active investing.

6. Easy to understand

If all of the above is not enough to convince you that most people should be using index funds for their investments, a further benefit is that index funds are easy to understand – you are just holding the entire market of publicly investable companies.

There is a saying that you should not invest in things you don’t understand. This is important because if you invest in something without understanding it, there can be unexpected consequences. The likelihood is very low that someone really understands how an active manager is investing, what it means the active manager is investing in risk-on or risk-off investments, what value vs growth means, how to evaluate their investment strategy, and how and whether they are sticking to their investment strategy.

Most that use active fund managers do so because they are unable to evaluate the investments themselves, but that also means they are usually unable to evaluate the fund manager and why they have chosen those investments.

In contrast, index funds are very simple to understand, even for someone who is just learning about investing for the first time.

Final thoughts

Index funds are easy to understand, even for new investors, they have extremely low fees and are more tax efficient, which improves performance, they are well-diversified, allowing you to avoid single-asset risk, and most importantly, allow you to avoid the high chance of underperformance of actively managed funds, all while consistently performing in the top quartile of funds.

Further reading

The case for low-cost index-fund investing – Vanguard

Why index funds are the optimal place to start – Lazy Koala Investing

10 Reasons I Invest in Index Funds – The White Coat Investor