When investing for children, or for any other goal, you need to:

- Define the purpose of the money. This will form the basis for deciding how to invest that money to best meet your goal and how much to save each month.

Then you will need to select the:

For those who are already familiar with asset allocation and the passive vs active discussion and want to get right to the structures, feel free to skip ahead.

1. Asset allocation

Your investing time horizon will dictate your asset allocation, which is the level of risk in your investment and translates to a ratio of growth assets such as stocks to defensive assets, such as cash or bonds.

An allocation of stocks-to-bonds of 50/50 means half your money is in growth assets, and half is in defensive assets. If there is a market crash and equities (another name for stocks) drop by 50% as they did during the GFC, a 50/50 allocation would only drop 25% overall – the first 50 in equities halving and the second 50 in bonds preserved. The flip side is that during a bull market, as we have had since then, you’ll only get around half the growth of a 100% equities portfolio.

If you won’t need the money for many years, growth assets, such as stocks, will give you a higher expected return. ‘Expected’ meaning the average over the long term but not guaranteed over the short-term. In contrast, for anything needed in less than three years, growth assets a not likely to be suitable, and more likely should be kept in cash – either a high interest savings account, a fixed-term deposit, or a mortgage offset account if you have one.

The longer your investment time horizon, the more growth assets you can tolerate because your capital can remain invested longer through any short term ups and downs to increase your chance of getting the long term average return of growth assets without the risk of having to pull your money out at a short-term low point.

The shorter your time horizon, the less short-term volatility you can tolerate, and the proportion of growth assets should be reduced accordingly. For instance, based on average historical returns, investing your savings for a house deposit in 100% stocks over a period of three years saves you on average three months, but due to the nature of growth assets, you risk a 50% loss of capital when you need it. So it is more sensible to just save for another three months and be sure you reach your savings goal.

In his book The Only Guide You’ll Ever Need for the Right Financial Plan, Larry Swedroe came up with these guidelines for the maximum percentage of your money invested in growth assets based on your investment time horizon (with the remainder in defensive assets like cash or bonds).

| Investment horizon (years) |

Maximum equity allocation |

|---|---|

| 0-3 | 0% |

| 4 | 10% |

| 5 | 20% |

| 6 | 30% |

| 7 | 40% |

| 8 | 50% |

| 9 | 60% |

| 10 | 70% |

| 11-14 | 80% |

| 15-19 | 90% |

| 20+ | 100% |

Summarising the above:

- For anything you will need within 3 years, growth assets are not suitable and should be in a risk-free investment such as a high interest savings account or a fixed-term deposit.

- With an investment time horizon of about 5-6 years, a conservative allocation of 30% growth assets and 70% defensive assets is a reasonable choice.

- At 10 years, an allocation of about 70% growth assets and 30% defensive assets is a good choice.

- And investing for way down the track, a high allocation of 80-100% growth assets is a good option.

From our two examples above, a high growth investment of 80-100% equities is most suitable for the house deposit 15 years away, and a high interest savings account or term deposit is most appropriate when saving for a car to be used within four years.

2. Investment management style

Simple, low-cost index funds have been shown to outperform the overwhelming majority (over 80%) of actively managed funds. And this is across geographical regions and time periods. If that’s not enough, out of those funds that outperformed the index over five years, 74.8% failed to outperform the market in the following five years.

Not only do they perform better most of the time, but you also remove the risk of a fund manager making a mistake by selecting poor investments. Time and time again, there are stories of fund managers that made monumental mistakes, sometimes resulting in billions of dollars lost to investors. Using index funds also removes agency risk — the risk that the management uses its authority to benefit itself at the expense of stakeholders.

And despite the enormous amount of sales and marketing out there, there is no evidence that active managers can stop you from losing money in a market downturn without reducing portfolio risk and therefore return — and if you are willing to reduce your return, you can achieve the same thing without manager risk by using a lower proportion of growth assets. The reason active managers cannot help you in a market downturn is that the stock market is forward-looking. Any bad news is priced in immediately before you or they have any chance to make any changes. Additionally, those who buy and sell more often, believing they can get in before it is priced in, get whipsawed so often that the chance of improvement is dwarfed by the likelihood of making a mistake resulting in worse performance. A fund manager (or adviser) telling you they can avoid losses without a commensurate loss of expected return is the biggest red flag for new investors who don’t understand that risk and reward are joined at the hip.

You also improve your risk-adjusted returns with broad market index funds due to the ability to remove unsystematic risk by diversifying into all types of companies in dozens of countries with just a couple of funds.

3. Structure

A structure is not an investment, it is a vehicle to hold your investments. Each structure is taxed differently, potentially resulting in significant tax savings with the right one. In addition, structures are useful in estate planning — making sure who gets what in case of your death, incapacitation, or if you are sued.

Structures can be a complex topic, and this is intended to provide you with a broad overview of the available options. It is not intended to be advice. You will need to determine by further investigation, either on your own or with an adviser or accountant, which option is most suitable for you before making a decision.

Structures

- Investing in the child’s name

- Investing in a low-income parent’s name

- Setting up a (informal) minor trust through a broker

- Debt recycling

- Offset account

- Setting up a (formal) discretionary/family trust

- Investment bonds (also known as insurance bonds)

- Investing in your super

- Investing in their super

1. Investing in the child’s name

This incurs very high tax rates to stop wealthy people from holding assets in their children’s name to avoid tax, so this is generally a bad idea.

| Income | Tax rates |

| $0 – $416 | Nil |

| $417 – $1,307 | 66% of the excess over $416 |

| Over $1,307 | 45% of the total income |

2. Investing in a low-income parent’s name

If one of the parents is in a low-income tax bracket and will remain that way, investing directly in that parent’s name and taking it out later to hand to the child when they have grown up will be a significant improvement on holding the shares in the child’s name. Although, this will require ‘realising’ any capital gains when transferred to the child.

[realising capital gains means paying out tax on capital gains to the government, as opposed ‘unrealised’ gains, which remain unpaid while you earn money on the delayed tax payment]

When do they get it? You have full control over when you gift it since you are both the legal and beneficial owner.

3. Setting up a (informal) minor trust through a broker

When investing in the name of the low-income earning parent, a capital gains tax (CGT) event is triggered when you transfer the investment to the child at age 18. With enough time and compounding, this could result in a significant tax hit.

However, several brokers allow the option to open a trading account as a minor trust account where you put down the parent’s name as the trustee and the child as the beneficial owner. The account name shows “parent’s name <A/C child’s name>“. When the child turns 18, ownership can be transferred to the child without triggering a CGT event. Instead, the child inherits the original cost base.

The advantage of this is that when the child turns 18, the shares are transferred to the child’s name without having to realise capital gains. If they have a low (or zero) income at that time, they could sell down the assets (potentially over multiple years, if necessary) and pay little or no tax from all the capital gains accrued over the years.

Using investments where most of the returns are in the form of capital gains rather than yield will accentuate this advantage. Some examples include:

- international shares — which tend to be more growth-focused, often as a result of share buybacks being more tax efficient

- small caps — which tend to be more growth-oriented due to the nature of small companies preferring to use earnings to grow their company rather than paying it out as a dividend

- certain funds that allow you to take your distribution in the form of more shares rather than as income, via DSSP (Dividend Substitution Share Plan) or BSP (Bonus Share Plan).

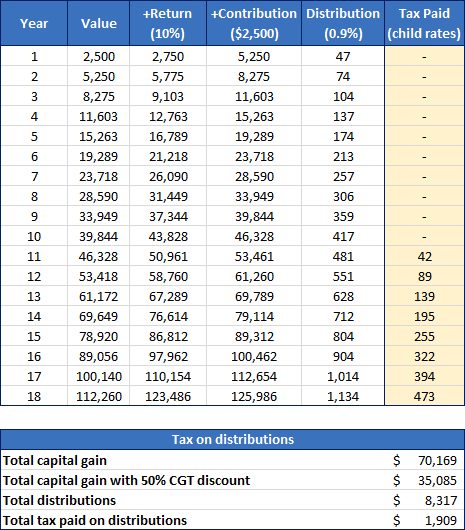

Here is an example using the following parameters:

- Starting amount and annual additions of $2,500

- Earning 10% p.a. return

- Using a diversified combination the above, which produces a weighted average yield of 0.90% at the time of writing.

The result is:

- Total taxable capital gain $70,169 ($35,085 with the 50% CGT discount)

- Total distributions $8,317

- The total tax paid on distributions is $1,909

With the 50% CGT discount, if the child at 18 was not working, they could sell down up to the tax-free threshold over two years, paying no tax on the $70,000 capital gain, and just $1900 tax on the $8,300 in distributions.

Some important notes:

- This is not a recommendation for any particular fund. It is to demonstrate the tax effect of using a minor trust while remaining properly diversified.

- The returns are projections. In reality, the stock market is volatile and can be up or down significantly in any single year or even over multiple years. The returns are using nominal values instead of inflation-adjusted values to demonstrate the tax effects.

- If you will be contributing significantly more than this, do the calculations because large amounts will breach the threshold of child tax rates resulting in high tax on distributions.

Some financial advisers and even ATO representatives on the ATO community forum say that you can open a minor trust account with the parents TFN and declare the income (from dividends) in the parent’s name and avoid the child tax rates of up to 66%. However, this appears to be incorrect. To get the benefit of transferring the capital gains cost basis with an informal trust, you must show that the trustee is simply holding the legal title and that the child is the real beneficial owner. This means the parent does not use the portfolio or dividends (including any franking credits) for their own purposes in any way, and any dividends are either reinvested through DRP back into the child’s account or deposited into the child’s bank account and not your own. Otherwise, the Australian Tax Office considers this proof that the parent is the real beneficial owner and the parents are liable for capital gains upon transfer of the shares. It then follows that tax must also be paid by the child in their own tax return (at their tax rates). In fact, this is from an ATO private ruling on this:

Under bare bones trust offered by brokers, a parent cannot lodge tax returns in their name and later pass the shares onto the beneficiary without CGT. You either lodge the annual tax returns in the child’s name and don’t claim CGT or you lodge annual tax return in the adults name and later incur CGT. Not both.

Check with your adviser or accountant to be sure. Although considering that many advisers and accountants get this wrong, a private ruling might be the best way to be sure.

When do they get it? A disadvantage of this is that the money is transferred to the child when they are 18, and at that time, they may not be responsible with money. Another problem is that shares count towards the Liquid Assets Test Waiting period (LATW) for Centrelink, so if they would otherwise be getting benefits like AusStudy, they may have to wait up to 13 weeks due to the LATW.

4. Debt recycling

If you have main-residence debt, debt recycling is an excellent option. Debt recycling is where you take the money you want to invest with, pay down non-deductible debt (e.g. your home loan), and borrow it back out before investing. Sending your money on a detour before investing so that you are using borrowed money to invest in income-producing assets results in the interest on that portion of your loan becoming tax-deductible.

Let’s say you had a home loan with an interest rate of 4%, and your marginal tax rate was 32.5%. Debt recycling results in the government effectively paying for 1.3% of that 4% interest on the amount you are using for investment, and you are only paying 2.7% interest. You could then consider that saved money as part of the child’s investment.

With debt recycling, the tax-deductibility of the interest reduces the taxable income of the share portfolio. Although, since it is in the parent’s name, this will require realising CGT when it is transferred to the child. But the amount saved on the home loan plus the savings from not paying child tax rates on the income may be enough to make up for this. It also provides flexibility in case you want to use or give the money sooner or later at your discretion.

When do they get it? You have full control over when you gift it since you are both the legal and beneficial owner.

5. Offset account

Another option if you have main-resident debt is to keep it in your offset account. As it is main residence debt, the return is your interest rate divided by your (1 – your marginal tax rate). For example, if your interest rate is 5% and your marginal tax rate is 34.5% (including the 2% Medicare levy), then your return is equivalent to a pre-tax return of 5%/(1-34.5%) = 7.63%.

The reason it is higher than 5% is that the ‘return’ you get is via reduced interest payments, and as this is not actual income, it is not taxed, so the above calculation gives you an equivalent return of what you would need to get from any other type of investment that would be taxed.

This has a lower expected return than debt recycling, but can be useful for shorter time frames like under five years.

When do they get it? You have full control over when you gift it since you are both the legal and beneficial owner.

6. Setting up a (formal) discretionary/family trust

For large amounts, consider a discretionary or family trust, which provides the ability to distribute income and capital gains to different members each year based on your family members tax rates at the time. Unfortunately, the costs of setting up and operating a discretionary trust are generally not worth it for small amounts but get advice on this if you have a large amount because it provides the most flexibility and can be very tax efficient. The cost is around $1,000 p.a. or more, so with $50,000 invested and growing at 10% p.a., that will be 20%+ of your annual returns going to administration fees, which is why larger sums are generally needed.

When do they get it? The trustee has full control over when income and assets are gifted (based on the trust deed).

7. Investment bonds (also known as insurance bonds)

An investment bond is a structure where the assets are not owned or taxed in the individual’s name but rather inside the investment bond, so it has no adverse effect on the owner’s income tax (either child or parent).

Despite marketing that makes it sound like it is ‘tax-free’, tax is paid within the bond at the corporate tax rate. And despite marketing making it sound like it offers great tax savings, there are often adverse tax consequences of using these compared to investing in your own name.

It is frequently pointed out that the tax rate within an investment bond is 30%, leading to the false conclusion that if your MTR is over 30%, it is automatically advantageous.

However, if you are using high growth investments (which would be the case when you cannot draw from it without penalty for at least ten years, such as with an investment bond), most of the returns will be in the form of capital gains. For someone even on the highest marginal tax rate of 47% (45% plus the Medicare levy), capital gains for assets held in your own name for over 12 months are taxed at 23.5% due to the long-term capital gains (LTCG) discount, whereas in an investment bond, it would be 30% since you lose the LTCG discount when using an investment bond.

Additionally:

- You lose the ability to sell down during years when on a low marginal tax rate to pay less tax

- Investment bonds tend to attract high fees

- There is a narrow range of investment options

- There are restrictions on how much you can contribute each year

- There are penalties for withdrawing from it within the first 10 years.

Unfortunately, many advisers seem to get their information on these products from providers of investment bonds (i.e., salesmen) and consequently don’t fully understand them. So you have to be careful even when going with an adviser to help with a decision on investment bonds.

Where investment bonds are beneficial is in estate planning and convenience because money put into an investment bond belongs to a different legal entity. For instance, if grandparents want to invest for their grandchildren and be sure the parents can’t get a hold of the money. Investment bonds may also be useful for those receiving the family tax benefit (FTB) since the income from investment bonds does not count towards the parent’s personal income, which reduces the FTB payment. You can also choose what age the investment is transferred to the child up to age 25.

Investment bonds are marketed as tax-efficient because they’re not taxed in the parent’s name, but you really need to do the figures because unless you are on the highest marginal tax rate, there’s almost always a more tax-efficient way.

When do they get it? You can often set the investment bond to be paid to them at an age from (18 to 25) of your choosing, but the child may be able to demand it from 18 as they are the beneficial owner, so check the details if this is a requirement.

Addendum: There is a category of investment bonds called ‘education bonds’. With this, tax is not taken if it is used for specified purposes under legislation. You still suffer the same issues mentioned above, but the possibility of zero tax may make up for this and more. Be sure to look carefully at exactly what you can get the tax exemption for because there are loads of people when you do an online search who didn’t understand and were very frustrated with locking up their money for 10 years only to find out they did not get the tax exemption.

8. Investing in your super

Investing in your super is one of the most tax-efficient and flexible ways of saving for children if you expect to reach preservation age before you plan to give them the money. This is because:

- you get an immediate (and significant) return on your investment by way of a tax deduction

- you get a lower tax rate on ongoing earnings

- once you reach preservation age, you can take it out, or leave it to grow tax-free until you decide the right time to give it to them.

Some things you might like to do if you go down this route:

- Use a separate super fund to make it easy to keep track of what money is for who.

- Use a low-cost industry super fund to minimise the effect of fees.

- Use a super fund that has an admin fee that is not a fixed fee (these are rare but do exist – CFS, Vanguard).

If you will not reach preservation age by the time you want to gift it to your children, another option could be a grandparent’s super account. However, there are aspects to be aware of before doing this:

- Age pension – if the grandparent is or will be receiving age pension benefits, this may reduce their benefit, and if they gift it to the child, under Centrelink’s gifting rules, that portion of the age pension may be reduced for five years from the date of the gift for amounts over $10,000 per annum or $30,000 per five years.

- You need to be able to trust that the grandparent will not spend it.

- If the grandparent dies or remarries and gets divorced, others may have a claim to it.

When do they get it? You have full control over when you gift it since you are the beneficial owner. However, the beneficial owner of the super fund must have met a condition of release before they can access it.

9. Investing in their super

Children can have superannuation accounts. Although, you cannot claim a tax deduction from your income, and they cannot access it for a very long time. Additionally, for small amounts, the fixed fee will eat into the assets heavily, so unless you are likely to put in a substantial amount, you will need to find a super fund with an admin fee that is not a fixed fee and that allows opening a child’s super account. Few funds offer this, but they do exist – Rest is one. If that is suitable, the compounding will be turbo-charged with a lower tax on earnings over six decades. If you do this, make sure the account remains active or it will be transferred to the ATO for safekeeping.

If you aren’t likely to reach the transfer balance cap in your own super (currently $1.7m), investing through your own super and gifting it to them later may be an option that is both more flexible and more tax-effective, but you have to watch out for the gifting rules on the aged pension benefit if that will apply to you (anything over $10,000 gifted in a single year or $30,000 gifted within a five-year period counts towards your assets and reduces your pension for five years).

When do they get it? When they reach preservation age (currently 60, but it is possible that it is pushed back in the future as the population ages)

Considerations in determining which structure to use

In deciding which structure to use, you need to take into consideration:

- Tax

- Timing of access and if you want to gift it beyond 18 when they are more financially responsible

- Estate planning

- How it may affect government support (FTB for you or AusStudy for them).

I would like to suggest seeking advice on the best option because the tax and estate planning consequences can be significant based on your situation. For instance, will you be retired when you plan to gift the shares? What will your marginal tax rate will be then? Do you want the option of choosing not to gift the money until a later date if they don’t turn out able to handle money responsibly?

However, due to the shocking things found in the advice industry over the years, ASIC now requires that personal advice (i.e., advice with product recommendations) to be provided in a Statement of Advice (SOA). An SOA is the 50+ page document that advisers give detailing your circumstances, goals & objectives, recommendations, reasons, alternatives considered, and all the calculations. An SOA is a legal requirement for personal advice (i.e., where there is a recommendation based on your personal situation). It takes a lot of time to prepare these documents due to compliance requirements, which drives up the cost of advice to the point of where it is unaffordable for most of the population, and almost certainly when you just want something simple such as help on how to invest for your kids.

If you don’t feel it is necessary for a recommendation, non-SOA general advice may be a worthwhile option exploring. This is where, rather than getting product recommendations, you just have your options explained to you and you make the decision. This is not common and it may be tough finding an adviser who will do it (and even tougher finding one that knows about investing for kids).

Teaching your child to fish

“If you give a man a fish, you feed him for a day.

If you teach a man to fish, you feed him for a lifetime.”

Rather than just handing your child the money when they are old enough, create a simple excel sheet showing the value each month and show them how the portfolio has done that month. Show them both the up and down months so they can get used to the market fluctuations. By the time they are an adult, they’ll not only have some capital, but they’ll also have an education in investing.

Final thoughts

Investing for children can really help them, especially with the way property prices have risen over the last two decades. You will need to decide on a goal, which will dictate how long and how much to save each month to reach your goal. Then you will need to decide on an asset allocation, investment management style, and which structure to use, based on your personal situation, tax outcomes, and when you want to gift the money. Additionally, you should consider spending time with them as they grow up so they can see how the market moves over time so that when they have money, they are more likely to invest it wisely themselves.