The risks

There are two currency risks.

Home currency upside risk

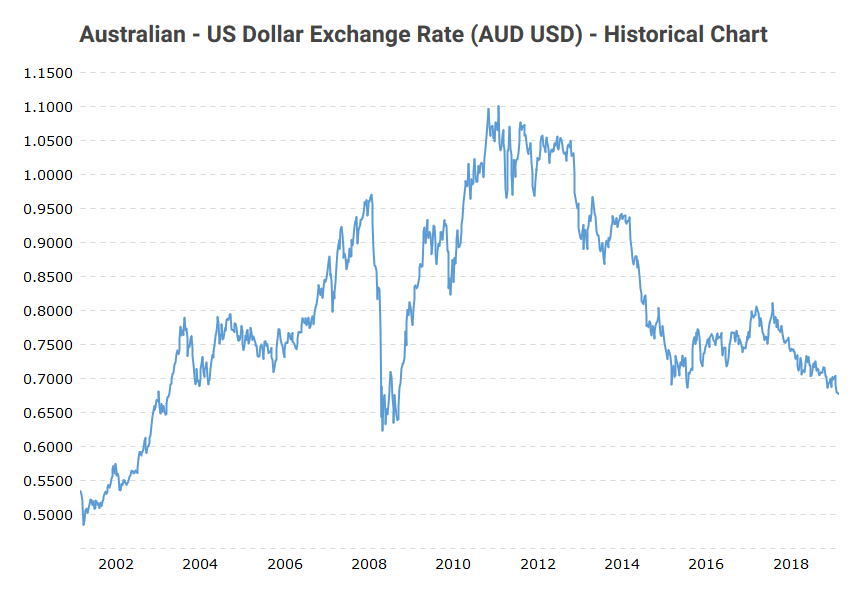

Home currency upside risk is where you have an all global portfolio, and your home currency rises against the world’s currencies. An example of this was from 2000 to 2011, where the Australian dollar more than doubled vs the US dollar, which means compared to an AUD currency hedged fund, it would have had half the value, and almost two decades later, it is still 1.5x what it was in 2000.

The problem with home currency upside risk occurs when Australian made goods and services rise in cost faster than our global portfolio, meaning when we drawdown, we will be drawing down more, depleting our portfolio faster.

Home currency downside risk

Home currency downside risk is where you have an all home-currency based portfolio, and your home currency loses ground vs the world’s currencies — basically, the opposite of the above.

The problem with home currency downside risk occurs as goods and services partly or wholly made or serviced overseas rise faster than our Australian dollar based assets.

To mitigate currency risks, we want both AUD based assets and non-AUD (global) based assets.

Bonds for safety, risky assets (stocks) for growth – tacking currency risk onto risky assets

Since stocks are the risky/growth allocation of portfolio and bonds are the safe allocation, it only makes sense that bonds are based in our home currency to avoid currency risk in low-risk assets. This is why bond funds that hold international bonds hedge them back into Australian dollars.

Since we are intentionally taking risk on the equities side to get the higher expected return, there is an argument that adding currency risk to our already risky allocation of risk assets isn’t much of an issue. In particular, this becomes a strong argument when you consider that as you get older, your risk tolerance naturally decreases and by the time you hit normal retirement age, you will often be in the neighbourhood of 50% stocks and 50% bonds, and if you’re diversified with an entirely global stock portfolio, you’re already evenly hedged against both risks.

This argument will suit a lot of people’s situation. However, problems with this come in for those who will be maintaining a more aggressive allocation. For instance, early retirees who will need a higher long-term return to support them for longer, those who plan to rent into retirement as they will have more AUD based liabilities, and the fact that Australians more generally have one of the lowest bond allocations in the world.

Other arguments against AUD based equities

There are a few other arguments that there is no need for home currency (AUD) based equities, and we should go for all-global equities, but I would like to offer some opposing arguments to these.

Argument 1 – It isn’t necessary because currency movements even out over time.

I’m not sure how to create a global currency basket and in the right proportions to match a global equities portfolio, so I’m going to use the USD as a global currency and the US market in place of the global market.

In the year 2000, the AUD was equal to 0.5 USD.

Over the next 11 years, it more than doubled. If you compared a US index fund vs an AUD-hedged version at the end of that period, you would have less than half the amount in Australian dollars.

Until 2018, almost two decades later, it was still over 1.5 times what it was in 2000.

The argument that currency swings eventually even out is most likely true (eventually), but that fact only helps if you can tolerate decades of currency headwinds on your portfolio. Even if you can tolerate it financially, I suspect few people can tolerate it emotionally and end up selling low and buying high only to see what they switch to, then underperform.

Argument 2 – Home country equities add concentration risk (lack of diversification).

This is absolutely true, and concentration risk is one of the big ones. By overweighting home country equities, you now have your job, housing, and investments all concentrated in the same market, which is quite a risk. However, firstly I would say that just because there are two opposing risks (currency risk and concentration risk) does not automatically mean that there cannot be a compromise to reduce the risk of any single risk devastating the portfolio. Secondly, we are fortunate that today we have an alternative option – global equities hedged into Australian dollars – which allows us to hold AUD based assets without concentration risk.

Argument 3 – There is a drag on returns due to the cost of hedging – an additional hidden cost to the management expense.

This Wisdom Tree paper notes that these days hedging is very cheap at the cost of around 2-3bps, so essentially nothing.

When you look at the wholesale version of VGAD (to get longer term data, plus it’s the underlying fund of VGAD), there is no drag on returns over the last ten years of returns available there.

In this Vanguard paper, the graph on page 4 shows that while most of the time hedging is around 2-4 basis points (just eye-balling that graph), that during the financial crisis, it went up to between 8 and 18 points for a couple of years.

However, a couple of years of 8-18 bps costs wouldn’t bring the average long term cost of hedging up much, and to avoid the decade-long (or longer) upward and downward cycles of the currency movement, the benefit of currency hedging still makes sense.

Argument 4 – In resource-rich countries such as Australia and Canada, currency hedging increases volatility.

This Vanguard paper shows an example of it occurring over one time period on page 7.

The paper is excellent, and one of the most well-explained papers I’ve read on currency hedging decision points, and I would urge you to read it thoroughly.

My issue is that when you look at the graph on page 7, it says annualised volatility, which means that hedging makes it go further up or down from one year to the next.

This can dangerously mislead your attention.

For instance, imagine yearly returns as follows.

Currency hedged

+4%, -4% +4%, -4% +4%, -4% +4%, -4% | +4%, -4% +4%, -4% +4%, -4% +4%, -4%

Currency unhedged

-3% -3% -3% -3% -3% -3% -3% -3% | +3% +3% +3% +3% +3% +3% +3% +3%

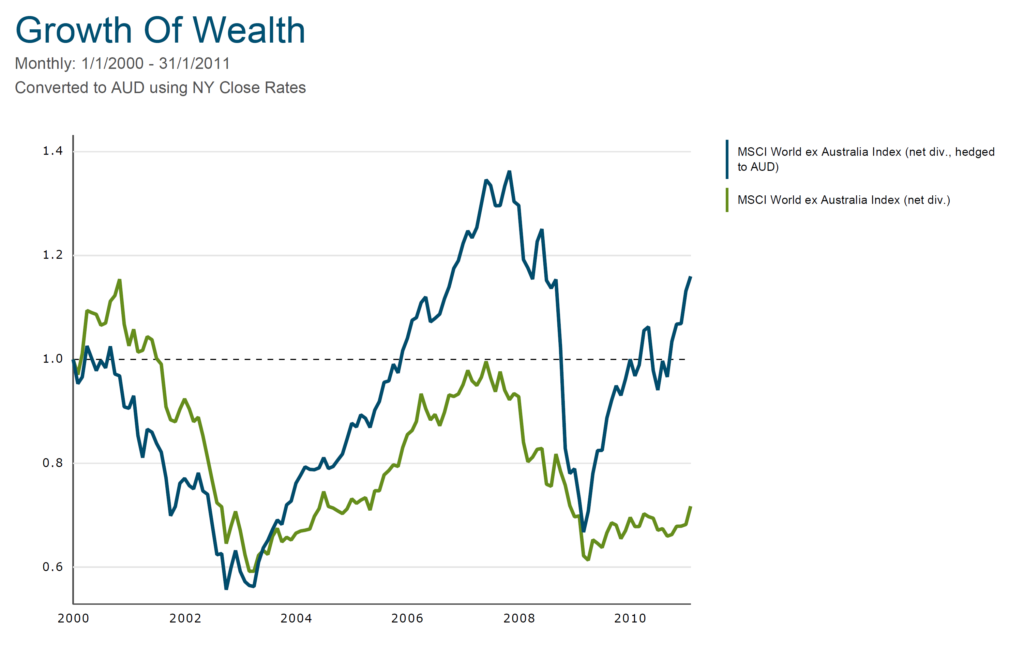

The hedged one has higher annualised volatility (i.e. from year to year), but the unhedged one will have a far more severe risk showing up during drawdown because the lower volatility was moving in the same direction for many years in a row.

This is precisely what happened from 2000-2011 (other than the brief fall in AUD vs USD during a market crash, before continuing on its 11-year upward trend).

Let’s see this in an image to make it more clear.

In the image below, you see that there is a flight to USD during a financial crisis. As a result, the AUD goes down at the same time as global equities, cushioning the fall in the value of your global stocks when measured in AUD, and currency hedging removes this cushioning benefit and increases volatility at that time.

However, focusing on this point obscures the fact that this occurred for a relatively short period and then reverted back and continued on its 11-year upward trend, where the exchange rate eroded the value of your global stocks by more than half vs the USD when measured in AUD.

When you’re retired and drawing down from your portfolio, cushioning the fall for a relatively short period is going to pale in comparison to hedging and avoiding excessively drawing down over a long period of a decade or more. And don’t forget that even though the AUD rose for 11 years, it is still well above the starting point almost two decades later, so without hedging, you would be depleting your portfolio faster for much longer than the 11 years it was rising.

The article, The Blunt Ratio, does a great job of explaining how short term volatility obscures your view of real risk.

Here is how this would have looked using the MSCI World ex-Australia Index against the equivalent currency-hedged version from 2000 to 2011, where the AUD more than doubled.

$100k at the start would have turned into either $72,000 (unhedged) or $116,000 (hedged).

Imagine how many people would see their international holding performing so badly for such an excruciatingly long period of time, giving up on it and selling it at a worse value than if they had left it in cash, earning nothing.

At this point, I remain unconvinced of these arguments.

- That currency movements are not an issue because eventually currency evens out;

- That concentration risk deters use of any home country or home currency bias;

- That currency hedging creates a significant drag on returns;

- That currency hedging sometimes increases (annualised) volatility as a useful argument for long term buy and holders.

There are still some good reasons against home currency bias besides these.

The main ones being that your home and your future earnings are in Australian dollars, so you have a lot of it covered without needing to tilt away from a global cap-weighted equities portfolio. Also, if you desire lower volatility in your portfolio (e.g. regular-aged retirees), generally you would have a higher allocation of safe assets (bonds), which should be either in your home currency, or currency-hedged if international, to reduce currency risk of your safe assets, and the lower the need for AUD based equities.

But you may still need AUD based equities. You may be retiring young and require a higher equities allocation to sustain you for more decades. You may have decided to rent instead of owning a house, leading to more AUD based growth assets to pay for your increased AUD-based liabilities (rent). So, there is a use for home currency equities.

You could wait until you’re closer to retirement to switch some of your global unhedged equities to an AUD-hedged version, but what do you do as you move closer to retirement? You could sell down your global equities and buy AUD based equities, but if the exchange rate is unfavourable at that time, you’re forced to time the market – and timing the currency market is about as successful as timing the stock market (i.e. not very). You could potentially use a glide path increasing each year steadily until retirement, but if you’re planning to retire early once you have the funds to retire, you don’t have a set date. To make it simple, I prefer just to create a more permanent allocation.

I would encourage you to read siamond’s Investing in the World series. Using long term historical data from a wide range of developed countries, he concluded that investors should probably build-in some home bias due to currency risk. A global equities fund hedged into AUD would likely offer the same benefit without the associated concentration risk.

Personalising your AUD to non-AUD allocation

Matching your liabilities to your currency allocation

If we assume housing costs are around 30% of expenses, and the rest split 50/50 between domestic and imported goods, that gives roughly 65% of total assets as the AUD target [30 + 0.5 x 70 = 65%]. Anywhere in the 50-75% range should be fine. You can come up with your own estimations; it doesn’t need to be exact.

An important point is that this proportion is based on your total net worth, including property, bonds, cash, Australian business.

Let’s say I have a home and investment property that together makes up 50% of my total assets, and say I had bonds or cash that are 15% of total assets. I’m already hedged into the Australian dollar and have met my target of 50-75% in AUD based assets, and there is no need for any concentration risk of adding Australian equities. An all global equities portfolio makes the most sense.

| AUD based assets (65%) | |||

| Property | 50% | ||

| Bonds | 15% | ||

| Non-AUD assets (35%) | |||

| Global equities (unhedged) | 35% | ||

Another example.

Let’s say you rented, so no home, and you had 25% of total assets in bonds, and let’s say you had the same 65% target. To reduce the currency risk of a high proportion in global unhedged assets, you would aim for about 40% in Australian equities or global AUD-hedged equities or a combination. But 40% making up over half your equities is quite a lot of idiosyncratic country risk in the concentrated Australian market, so instead, we could split it up into half each.

| AUD based assets (65%) | |||

| Bonds | 25% | ||

| Australian equities | 20% | ||

| Global equities (AUD-hedged) | 20% | ||

| Non-AUD assets (35%) | |||

| Global equities (unhedged) | 35% | ||

An important point regarding your AUD to non-AUD allocation is homeownership. Suppose you currently don’t own a home. In that case, it may appear that your equities allocation should be tilted more towards AUD based assets to meet your higher AUD based liabilities (future rent expenses). However, if you’re likely to own a home by the time you retire, then even if you don’t currently own a home, it’s worthwhile factoring into your future liabilities that you won’t need to be producing AUD based rental income in retirement, leaving you with something closer to a 50/50 split.

A further point about home ownership is whether you will be using income from your investments to pay for loan repayments. It’s generally recommended to deleverage when you retire, but if you are carrying a lot of debt once retired and that debt will be serviced by your investment income, you may need an increased proportion of AUD-based assets.

Australian equities vs global equities hedged into AUD

Australian shares have had a low correlation to global developed shares, which adds weight to the argument for including Australian shares above the 2% cap-weighted global allocation. You can get a lot of the benefit of low correlation with a modest allocation, though. For example, Vanguard found that US investors can get most of the diversification benefit of non-US shares with just a weight of 20% ex-US shares. So 15-25% Australian shares should give you a lot of the diversification benefit while keeping concentration risk down.

My preference is no more than 20-30% of total equities to be Australian equities, and the rest of the AUD portion in global AUD-hedged equities. I just don’t consider the risk of any more than this in such a concentrated market like Australia worth the franking credits (even if they turn out to be not entirely priced in). If the Australian economy takes a hit and I have no more than 30% of my equities in Australian equities, my total portfolio will be far less severely affected.

As an example of what can go wrong, the UK index, for example, dropped 73% back in 1973-74. They were a developed country, and I’m sure that a good amount of equities in the UK index looked relatively safe in backtesting at that point. Those who remember what happened would have a very different opinion to many who recommend 50-100% in Australian equities. Then, of course, there is Japan, where after three decades it has still not come close to where it was in 1990. Just looking at the graph makes my eyes bleed. How much concentration risk are your franking credits really worth?

This Vanguard paper on hedging vs not hedging discusses that as investors are learning the value of global diversification and consequently reducing home bias in their equities, the result is larger foreign currency exposure, and currency hedging should be considered.

Below are the three different asset classes of equities and their benefits and drawbacks.

| Global equities | Australian equities | Global equities AUD-hedged | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitigates concentration risk |  | Has concentration risk |  | Mitigates concentration risk |

| Mitigates downside currency risk |  | Has downside currency risk |  | Has downside currency risk |

| Has upside currency risk |  | Mitigates upside currency risk |  | Mitigates upside currency risk |

| No franking credits |  | Has franking credits |  | No franking credits |

Too much global equities expose us to currency risk.

Too much Australian equities expose us to concentration risk.

This is where global equities hedged to AUD comes in to fill the gap. It comes at the cost of franking credits, but franking credits come at a cost of concentration risk. You cannot eliminate risk; you can only transform it into another risk. My preference is to moderate the risks to avoid any single risk overwhelming my portfolio.

Final thoughts

You now know the fundamentals of designing your passive portfolio by sticking to index funds and answering 3 questions.

- Your equities to fixed income allocation based on your risk tolerance.

- Your AUD to non-AUD asset allocation based on your total wealth and liabilities.

- How much you want in Australian equities vs global equities AUD-hedged based on franking credits vs concentration risk.

Deciding what to invest in really is as simple as answering those 3 questions.