Before we begin, investment bonds are different from bonds.

Bonds are an investment where you loan your money out.

Investment bonds are an investment vehicle or legal structure like managed funds, LICs, or superannuation, which holds investments such as stocks, bonds, etc. Investment bonds are offered by insurance companies/friendly societies.

They are marketed as having no personal tax to pay if you don’t withdraw until after 10 years. The reality is that it is tax-paid, meaning that tax is paid within the bond. If you had to pay personal tax on top, you would be paying tax twice.

Investment bonds, also known as insurance bonds, are actually life insurance policies – minus the insurance part.

A bit of history

There are four types of life insurance in Australia – term life (death) insurance, total and permanent disability insurance, trauma insurance, and income protection insurance.

They are all pure life insurance products, meaning there is no investment combined with it. You only pay for the part that pays out in the case of illness, injury, or death. Otherwise, you get nothing back. Premiums are much lower to reflect this.

However, once upon a time in Australia (and still in many other countries today), an insurance product called whole-of-life insurance combined insurance with investment. They are generally opaque – you don’t know how much of your investment is used to pay for the premiums, or how much you pay in fees for the investments. They are invested conservatively to preserve the funds in there, which results in low returns and is a massive drag on returns over the long term. The main benefit is that there is generally always money available for the insurance premiums, so premiums can’t accidentally lapse and leave you uncovered. And for those who otherwise would never have invested any money, they would have some money regularly set aside for later in life, although this last point has been replaced by super.

If you read investing and personal finance websites from the US, where these are still offered, any time you read of someone saying to avoid some terrible insurance product, it’s pretty much always whole-of-life insurance.

Since the ’70s, whole-of-life insurance in Australia has steadily disappeared, although legacy whole-of-life insurance policies still exist. Whole-of-life insurance in Australia has been separated into more flexible and transparent pure insurance and investment products. The investment part is investment bonds ( insurance bonds).

The tax benefits effects of investment bonds

Investment bonds are marketed as a tax-efficient investment because no tax is payable by the individual (provided it is held for at least ten years). It is internally taxed at the corporate tax rate of 30%. It sounds like a fantastic tax-advantaged investment vehicle for anyone with a marginal tax rate over 30% and investing for the long term (over ten years).

Let’s take a closer look.

Shares are one of the most tax-effective investments available. Two reasons for this are:

- The 50% CGT discount

If an individual has held shares for more than 12 months before selling, 50% is taken off their capital gain before adding it to their income tax return. - The ability to delay paying tax and sell down when on a lower marginal tax rate

You do not pay tax on capital gains until the shares are sold, and far less tax can be paid by waiting to sell until retirement when you are on a much lower marginal tax rate.

These benefits are lost when using investment bonds.

1. Losing the 50% CGT discount

The 50% CGT discount can be used by individuals but not by companies. Provided shares are held for longer than 12 months, a person on the highest marginal tax rate of 47% (including Medicare levy) would have capital gains taxed at 23.5% in their own name compared to the company tax rate of 30% within an investment bond. And that is for the top 5% of the population on the highest marginal tax rate. Losing the 50% CGT discount and paying 30% tax has an even bigger negative impact the lower your marginal tax rate.

2. Losing the ability to delay tax paid and sell down when on a lower marginal tax rate

Since everything is taxed at 30% within the bond, you cannot take advantage of waiting to sell down when you are on a lower marginal tax rate. Although you may be able to lessen the downside of investment bonds somewhat by redeeming them early if you meet a specific set of circumstances.

What about the income component of investments in investment bonds?

Yes, there is an advantage with the income component of investments within investment bonds while you are on a marginal tax rate over 30% because the benefits of shares mentioned above do not apply to income. But selecting tax-inefficient investments just so that they can be a bit less tax-inefficient (but still tax-inefficient) doesn’t make sense.

And whilst investment bonds are cheaper than they previously were, they’re generally more expensive than other investment avenues such as direct investment or even superannuation. With defensive assets generally having lower returns, the additional fee can pretty quickly negate any potential tax saving.

For long term investing, you want the majority of your investments in tax-effective growth assets due to the 50% CGT discount, the ability to earn and compound returns on delayed tax payable, and the ability to sell down when you are on a low marginal tax rate. However, the higher the capital growth component to make use of these advantages, the worse investment bonds perform.

The article below is one of the better ones, showing an apples-to-apples comparison that you’re worse off tax-wise with an investment bond unless you are on the highest marginal tax rate. If you select investments with a lower capital gain component, the investment bond nudges slightly ahead for someone on the second-highest marginal rate, but as mentioned above, it doesn’t make sense to use low growth products when investing for such a long period of at least 10 years as required with investment bonds.

The strategic fit of investment bonds – Part 1: timeframe of 10 years or more | Macquarie

But these numbers are all theoretical!

Many analyses (such as in the one linked above) use theoretical numbers and approximations, which come up with similar negative results for investment bonds. But with approximate numbers used in theoretical scenarios, investment bond providers can (rightfully) claim that the assumptions and nominal return figures used in the analysis are not realistic, so the results can be taken with a grain of salt.

If we are using real world numbers that show how poor investment bond returns are, there is no longer any argument.

Thanks to ghostdunks for doing just that in the following post.

Investment Bonds as a tax-paid investment compared to holding equivalent ETF directly : AusFinance

But investment bond advertising says they have an effective tax rate of much lower than 30%

Any investment held by an Australian resident (company, trust, or individual) is eligible to receive franking credits.

Let’s say an investment bond held Australian shares that paid fully franked dividends, and let’s say the dividends were 4% (roughly what the Australian index pays). The franking credits that are refunded would result in an income of 5.7%. If the investment bond is taxed at 30% of the 5.7%, that comes to a 4% after-tax return on those dividends. The capital gain, as well as any distributions that were not franked, would be taxable, so the overall effective tax rate would be above zero, but the franking would reduce your effective tax rate significantly.

However, as this benefit is available to all Australian residents, not just in investment bonds, using investment bonds does not provide any advantage in this regard. If you own Australian shares, your own effective tax rate is also lower.

In addition to franking credits, your own effective tax rate is likely to be far lower than your current marginal tax rate due to what was mentioned above – the 50% CGT discount and the ability to sell down once retired and on a much lower marginal tax rate.

Investment bond advertising routinely quotes an effective tax rate much lower than 30% because they rely on the fact that almost nobody understands this, and they just see a low number for the tax rate and think it shows that investment bonds are tax effective. It is designed to mislead customers into thinking investment bonds are more tax-effective than they really are.

Fees

Investment bonds have high fees. If you take a look at the largest provider in Australia, GenLife, they have a 0.60% fee [1] on top of the investment fee. A significant drag on returns.

If you were to buy an Australian index fund or a global index fund (e.g. VAS or IWLD), you would be paying 0.10% of your assets per annum in fees.

If you bought the same product through GenLife, for instance iShares Australian Equity Index Fund or iShares Wholesale International Equity Index Fund, the cost is a whopping 0.70% of your assets per annum.

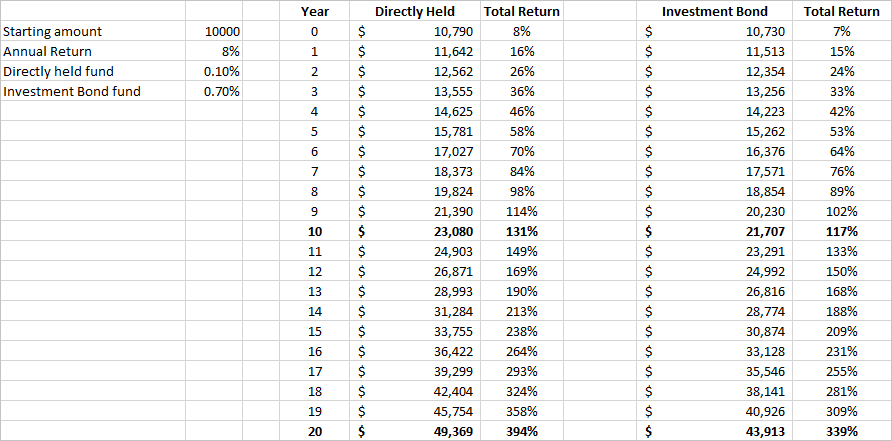

Let’s take a look at what you get over ten and twenty years based only on the higher investment fee. This ignores all the lost tax advantages mentioned above.

As you can see, over ten years, there is a 117% gain vs a 131% gain, so 14% of the initial investment has been lost in returns due entirely to the higher fee.

Over 20 years, a whopping 55% of the initial investment has been lost in returns due to fees alone. This is in addition to the tax issues mentioned above.

More problems

Besides the tax-related downsides for anyone other than those on the highest marginal tax rate (or for a couple, where both are on the highest marginal tax rate), and the high fees, investment bonds also:

- have a much narrower range of investment options

- have restrictions on how much you can contribute each year (max of 125% of previous year’s contribution)

- have restrictions on when you can withdraw from it (tax penalties for withdrawing before ten years).

In terms of the tax effects of withdrawing from the bond within ten years, the rule is:

- Within the first 8 years, 100% of the earnings on the investment bond are added to your assessable income in that financial year, with a 30% tax offset for the 30% tax paid within the investment bond.

- After 10 years, none of the tax is added to your assessable income, but what you get paid out is after 30% tax has been paid within the investment bond (and without the CGT discount).

- During 9th year, 2/3 of earnings on the investment are treated as if you withdrew within the first 8 years and the remainder is treated as if you withdrew after 10 years.

- During 10th year, 1/3 of earnings on the investment are treated as if you withdrew within the first 8 years and the remainder is treated as if you withdrew after 10 years.

As you can imagine, withdrawing many years of earnings before the 10-years is up could end up costing you even more than the high fees and lack of CGT discount – it could push you up into the next marginal tax rate. The flip side is that if you have a year of low income (e.g., maternity leave), you have a chance to get out of this product.

Borrowing to invest is a common strategy because the interest is tax-deductible (the same idea as negative gearing property). Borrowing to invest in investment bonds are sometimes put forward as a doubly tax-effective investment. Unfortunately, along with the investment bond not being tax-effective for most people as explained above, the interest when borrowing to invest in investment bonds is also not tax-deductible due to the investment bond not being taxed in the individual’s own name – another downside to investment bonds vs investing in your own name.

Are they still useful?

Where investment bonds are beneficial is in estate planning and convenience because money put into an investment bond belongs to a different legal entity.

If you put money into an investment bond and nominate a person (e.g., a child) as the beneficiary, you are not the legal owner of that money and in case of death, divorce, or litigation, that money does not form part of your assets. This provides several useful scenarios.

One such scenario is for grandparents who want to invest for their grandchildren and be sure the parents can’t get a hold of the money. This is because money added to an investment bond is legally an insurance premium, and the person paid out the life insured. A discretionary trust could be a useful alternative, but there are high costs and complexities to set up a discretionary trust, so an insurance bond may be a simpler solution for those without substantial amounts of money. In that case, it would be a trade-off between all the issues mentioned above versus ensuring that in the case something happens to you, the investment proceeds will go to the right person.

Another use is for those in professions with a higher chance of being sued such as doctors, dentists, and lawyers. Since the investment bond is an insurance policy and not an asset held in one’s personal name, there is a level of protection from creditors. This is provided it wasn’t obviously used as a way to avoid creditors. For instance, if you deposited a large amount into investment bonds shortly before you went bankrupt, there is a higher chance the court could see through that. A discretionary trust or super (which is also a trust) offers a similar level of protection, but a discretionary trust costs more to run and super is inaccessible until preservation age.

A further use that since investment bonds do not form part of your estate, they are not distributed under a will and cannot be contested. Again, this is to ensure the proceeds go to the right person, which is the common thread and is the what estate planning is about.

Another use of investment bonds can be the impact on government benefits. For instance, Family Tax Benefit (FTB) could be a factor affecting couples with young families in regards to the decision of investing using an investment bond (where you incur no personal tax liability) vs investing in a minor trust (mentioned in the next paragraph) where it is added to your taxable income and therefore may reduce FTB payments. If you’re within the thresholds to get both FTB-A and FTB-B, you may lose an equivalent of 20% of the investment’s income returns from each of those. So remember to factor that in if you’re getting means-tested government support when doing calculations to weigh up your options.

If you’re looking for an investment for your kids, another option to consider is a minor trust account through a broker. A minor trust account avoids the many problems of insurance bonds (high fees, lack of CGT discount, restrictions on how much you can contribute, restrictions on when you can withdraw, etc.). The big advantage of a minor trust is that the child doesn’t need to realise capital gains when it is transferred to them until they sell, which could be years or decades later. And if they sell during low- or no-income years (e.g. at 18 as a student) their tax rate may be so low as to be able to pay little or no tax on the capital gains from all those years.

To get the benefit of transferring the capital gains cost basis with an informal trust, you must show that the trustee (e.g. parent) is simply holding the legal title and that the child is the real beneficial owner. This means the parent does not use the portfolio or dividends (including any franking credits) for their own purposes in any way, and any dividends are either reinvested through DRP back into the child’s account or deposited into the child’s bank account and not your own. Otherwise, the Australian Tax Office considers this proof that the parent is the real beneficial owner and the parents are liable for capital gains upon transfer of the shares. It then follows that tax must also be paid by the child under their own TFN (at their tax rates). In fact, this is from an ATO private ruling on this:

Under bare bones trust offered by brokers, a parent can not lodge tax returns in their name and later pass the shares onto the beneficiary without CGT. You either lodge the annual tax returns in the child’s name and don’t claim CGT or you lodge annual tax return in the adults name and later incur CGT. Not both.

However, note that with investment bonds, you get to choose what age the investment is transferred to the child up to age 25. So that is another consideration.

Check with your adviser or accountant on the best structure to use when investing for a child. Although considering that many advisers and accountants get this wrong, a private ruling might be the best way to be sure.

Alternatives to investment bonds for tax-effective investments

Contributing to your super

Contributing to super is the obvious alternative as you get a massive boost due to paying less tax. However, it is locked up until preservation age (60), so investment bonds are typically marketed as an alternative.

Investing in a low-income earner’s name

If either partner has an income below the top marginal rate, this is a more tax-effective alternative while also retaining the flexibility of accessing the money before preservation age (and at any time, unlike with an investment bond).

Debt recycling

If you have a home mortgage, you will get a better return from debt recycling than from an investment bond, which is paying the money into the loan and then redrawing it out to use for investment. By sending on this detour before investing in income-producing assets, you get a tax deduction on that portion of your loan for the life of the loan, boosting your investment return significantly.

Offset account

An offset account on your home loan provides a strong return at no risk while retaining full access to your money at any time. The reason it offers such a good return is that, unlike money that is in a bank account, where you have to pay tax on the interest at your top marginal tax rate, the return on an offset is not a cash payment but rather a savings of interest that you would pay. As a result, there is no tax to pay on it.

For instance, if your loan is 6% and your marginal tax rate is 47% (including the 2% Medicare levy), your effective rate of return is 6%/(1-47%) = 11.3%.

However, it should be noted that while this return sounds unbeatable, the previous option – debt recycling – has the same additional return advantage along with other advantages such as:

- the risk premium of stocks – typically about 5-6% over the central bank’s official cash rate, or 3-4% over mortgage rates

- returns on delayed taxes on capital gains (and the long-term compounding of these returns)

- the ability to sell down investments in retirement on a low or zero tax rate

- the 50% CGT discount

- franking credits

Setting up a (informal) minor trust through a broker

If the investment is for your child, several brokers allow the option to open a trading account as a minor trust account where you put down the parent’s name as the trustee and the child as the beneficial owner. The account name shows “parent’s name <A/C child’s name>“. When the child turns 18, ownership can be transferred to the child without triggering a CGT event. Instead, the child inherits the original cost base.

The advantage of this is that when the child turns 18, the shares are transferred to the child’s name without having to realise capital gains. If they have a low (or zero) income at that time, they could sell down the assets (potentially over multiple years, if necessary) and pay little or no tax from all the capital gains accrued over the years.

Using investments where most of the returns are in the form of capital gains rather than yield will accentuate this advantage. Some examples include:

- international shares — which tend to be more growth-focused, often as a result of share buybacks being more tax efficient

- small caps — which tend to be more growth-oriented due to the nature of small companies preferring to use earnings to grow their company rather than paying it out as a dividend

- certain funds that allow you to take your distribution in the form of more shares rather than as income, via DSSP (Dividend Substitution Share Plan) or BSP (Bonus Share Plan).

Setting up a (formal) discretionary/family trust

For large amounts, and where you can distribute to someone on a lower income, consider a discretionary or family trust, which provides the ability to distribute income and capital gains to different members each year based on your family members tax rates at the time. Unfortunately, the costs of setting up and operating a discretionary trust are generally not worth it for small amounts but get advice on this if you have a large amount because it provides the most flexibility and can be very tax efficient. The cost is around $1,000 p.a. or more, so with $50,000 invested and growing at 10% p.a., that will be 20%+ of your annual returns going to administration fees, which is why larger sums are generally needed.

Final thoughts

Investment bonds are terribly tax-ineffective for anyone but those on the highest marginal rates due to losing the CGT discount, loss of ability to earn returns on future tax payable, and loss of ability to leave it invested until you are on a lower marginal tax rate such as in retirement. They also have high costs further reducing any potential benefit, restrictions on how much you can contribute, and restrictions on when you can withdraw from it.

Holding the investments in the name of a low-earning spouse, or distributing via discretionary trust, gives you the benefit of the CGT discount, as well as the tax-free thresholds during the life of the investment.

Additionally, if you have non-deductible debt such as PPOR debt, you can take advantage of debt recycling to offset income gains from a diversified investment without the issues associated with using an investment bond.

However, if you are looking for a way to ensure a specific person receives the money, or if you are getting government support, you will need to consider the pros and cons. Don’t forget to investigate the use of trusts as an alternative option.

Recommended reading

Investing for Kids (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly)

Investing for kids (Part 2) – The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

Investment Bonds – GenLife – AussieFirebug (specifically, the comments by @keith_invests)

Investing for a baby and not touching till 18 – Whirlpool

Investment Bonds as a tax-paid investment compared to holding equivalent ETF directly : AusFinance

The strategic fit of investment bonds – Part 1: timeframe of 10 years or more | Macquarie

The strategic fit of investment bonds – Part 2: split portfolios | Macquarie

The strategic fit of investment bonds – Part 3: timeframe of up to eight years | Macquarie

1 0.60% fee up to $50,000, 0.40% next $450,000, 0.30% next $2,000,000.