The main asset classes are stocks, property, commodities, bonds and cash.

You may consider stocks and bonds to be lacking diversification since it’s only two asset classes, and I agree that it would be far better to be more diversified between different asset classes.

Unfortunately, there are implementation challenges with several other asset classes you should be aware of.

Quick Links

1. Property

Listed property

These are known as REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts), and you buy and sell shares in these companies on the stock market just like any other stocks.

The price is determined by the market and therefore tends to be highly correlated with stocks rather than directly owned property, so most of the diversification benefit is lost due to the fact that it is listed.

Also, many REITs invest in commercial property, so they’re exposed to the business cycle instead of the residential property cycle, again making them more highly correlated with stocks than with property.

Broad market indexes also already contain REITs, with global indexes having about 4% and Australian indexes having around 8% as REITs.

A deeper dive into REITs is available here.

Unlisted property trusts

These are generally illiquid and difficult to buy and sell.

They are also not subject to any listing rules or ASICs ongoing market supervision.

They are hard to accurately price without the market pricing it, and their information is intentionally hard to find, so you need to be an expert to know how to pick the sales and marketing from what you’re really likely to get.

Besides the problems with individual unlisted property trusts, the entire sector can be hit severely in a crisis.

Here’s an article from back in 2010.

Today, many unlisted property structures are frozen, many are struggling with excessive debt, some have been forced to cease distributions and there is uncertainty about the value of unit-holders’ investments if properties are sold on the open market.

This has happened before. After the complete collapse of the unlisted property sector at the start of the 1990s, it seemed inconceivable that they would return to popularity — but they have.

During the global recession at the start of the 1990s the property market crashed. Redemption queues immediately formed for unlisted property funds and, one by one, trusts froze their redemptions.

Investors found themselves in the stressful position of not knowing when they would be able to access their funds or what value they would ultimately receive.

When markets turn, getting your cash from an unlisted trust can be a nightmare. Some pre-GFC trusts were still waiting to pay 10 years after the GFC. Nothing will teach you the value of liquidity like holding unlisted property trusts when it turns sour.

In a nutshell, investing in unlisted real estate funds incurs due diligence, high management expenses, high transaction costs, multi-year periods of locking up capital, and a lack of transparency on current asset values given lagged valuations. If all that isn’t bad enough, you also face severe idiosyncratic sector risk.

Direct residential property investing

The stock market is pretty efficient, so you’re going to have a tough time beating it, and as such, just buying the entire market to guarantee the average market returns is often the most efficient way to invest.

The residential property market is inefficient, which means if you know what you’re doing, there are more opportunities to do better than the market average. The flip side of this is that if you don’t, you have more opportunity to do worse than the market average.

Then there is the lack of diversification with an enormous amount of your wealth in a single asset in one location. It’s virtually impossible to diversify through multiple property types, markets, and countries, so if you pick the wrong one or have a bit of bad luck, your total wealth can take a massive hit.

Further to the problem of a lack of diversification is that you already have an enormous amount of your wealth in direct residential property if you own your own home. Purchasing further direct property is going to increase your concentration risk even further.

There are also never-ending problems with tenants, incompetent property managers, changing tax laws.

Then, of course, there’s the illiquidity. If you need to cash some of it in, you can’t just sell a door or a window, so cash flow requirements are a problem. Another consequence of the illiquidity is that to sell any of it, you need to sell it all, and your CGT bill cannot be spread over multiple years. Consequently, it drives your tax bracket through the roof for most of your profit. Not to mention, when you do want to sell, it takes months.

Direct residential property investment isn’t necessarily a bad investment; it’s just that it takes a specific set of skills. If you understand the property cycle, economic cycle, the market you’re looking to invest in, have enough information and experience to take into account all of the variables, and a willingness for the work required, these market inefficiencies can work in your favour. The problem comes in for those who are looking for passive investment while you focus on other things in your life, such as family or building a career or business.

Direct commercial real estate

All the above plus potentially very long periods of vacancy. It’s not at all uncommon for a commercial property to be vacant for years.

2. Infrastructure

Similar to property, listed infrastructure behaves much more like stocks than unlisted infrastructure, so you don’t get much of the diversification benefit, and unlisted infrastructure is difficult for individual investors to even get into, is not subject to any listing rules or ASICs ongoing market supervision, brings illiquidity, a lot of unclear and misleading information, and requires expertise to determine a fair price.

Here’s how ASIC summarises the difference between listed and unlisted investments.

| Listed entities | Unlisted entities |

|---|---|

|

|

In a nutshell

- The downside of listed entities is that they are still essentially shares that go up and down with the share market, so you’re losing a lot of the diversification benefit.

- The downside of unlisted entities is that your information is essentially marketing information by the entity you’re buying from, and it is not overseen by a government body, so you need to be an expert to separate the facts from the marketing.

3. Commodities (gold)

Over time, governments print more money so that money devalues, as a way to get people to stop hoarding cash and instead spend it so that spending can drive the economy.

The result is that over time, you need more dollars to purchase the same item (a suit, milk, shoes, etc.), but even though you pay more dollars, it is not that the item has become more valuable, it is because the dollar has lost value.

Think of commodities such as gold as timeless non-perishable versions of these. They maintain their value even though the value of money goes down over time.

So, over the long term, commodities tend to track inflation, so you get a similar return to what you would if you invest in cash and add on the risk-free interest rate that comes with it. I.e. both gold and cash have a real (inflation-adjusted) total return of zero.

However, over the short and even medium-term, the volatility (i.e. risk) of commodities such as gold is very high, so it is too volatile for your ‘safe’ asset allocation, and the return is too low for your ‘risky/growth’ allocation.

You need the ability to hold during enormous volatility and during potentially decades of underperformance.

The following is stolen from Grok’s tips.

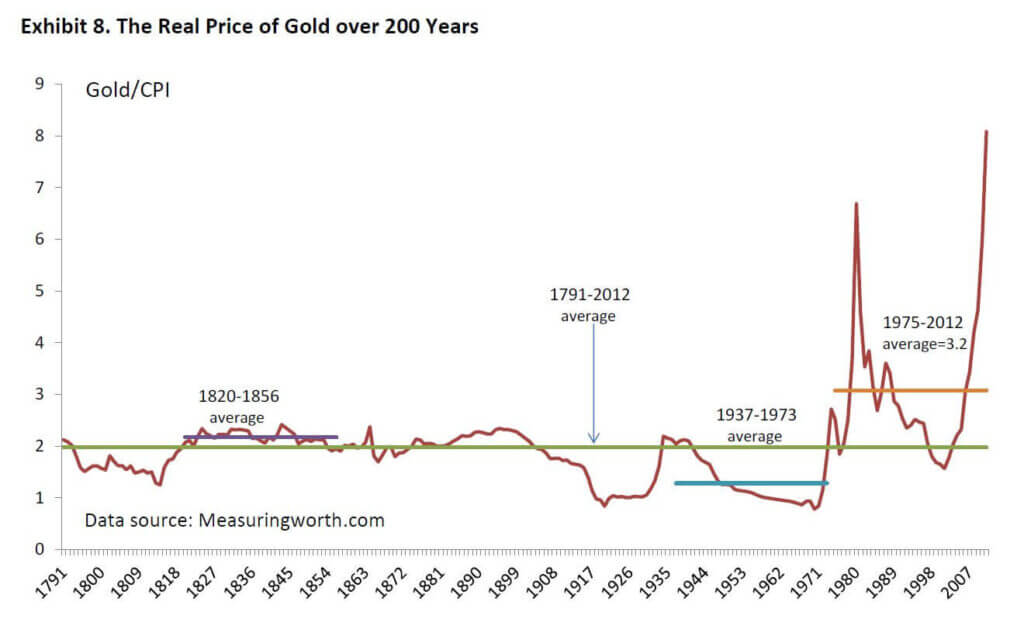

Here’s a chart I like to look at whenever I get the urge to invest in gold.

Inflation Adjusted Annual Average Gold Prices (1914-2014)

This chart shows what intuitively one would think. The expected real return of holding Gold is zero. Actually it’s worse than that since the chart ignores costs – either the expense ratio of an ETF like GLD or the storage/vault costs of physically owning gold. The red line shows the “real” (I.e. inflation adjusted) average price of Gold in 2010 dollars. Looking at the chart, the real price of gold went nowhere from 1914-2004, a 90 year period. Let’s break that 90 year period into six 15 year periods. Reading off the chart here are some rough numbers:

Year……Real Price of Gold (2010 dollars)

1914.……450

1929.……250

1944.……450

1959.……250

1974.……600

1989.……750

2004.……450

Annualized 15 year real returns

1914-1929–3.84%

1929-1944 4.0%

1944-1959–3.84%

1959-1974 6.0%

1974-1989 1.5%

1989-2004–3.35%

Mean0%

Std. dev.4%

Range-3.84% to 6%

So while the expected real return of gold is zero (ignoring costs) the risk of gold in real terms is enormous. Over 15 year holding periods sometimes your money was almost cut in half and sometimes it more than doubled!

I had a comment that the above quoted section conveniently ignores the price of gold post-2004 despite the chart going to 2014, and as a result, gold does, in fact, have a return above inflation. Maybe two centuries of data will be more convincing of the fact that gold has no return above inflation. The below image is from this paper.

Larry Swedroe points out in this article that as you can see from the recent 30 years, while gold protects against inflation in the very long run (100+ years), 10 years – or even 20 years – is not the long run.

If gold starts way above its long-term real value of zero, you can eventually expect gold to have a negative return compared to inflation, making the inflation-hedging of no use.

Not only that, it can overshoot or undershoot its long term real value for a very long time, again making the inflation-hedging worthless in decades-long investing time spans.

Here’s what Peter Bernstein, from his book The Power of Gold, had to say on how ineffective gold is an inflation hedge over even multi-decade periods:

The cost of living doubled from 1980 to 1999 – an annual inflation rate of about 3.5 percent – but the price of gold fell by some 60 percent. In January 1980, one ounce of gold could buy a basket of goods and services worth $850. In 1999, the same basket would cost five ounces of gold.

Gold is only a good inflation hedge over timeframes far longer than your investment horizon. It’s only over very long periods (100+ years) that gold is useful as an inflation-hedge.

All of this doesn’t in and of itself make gold a poor investment if the low correlation between gold and both equities and bonds improve your overall portfolio volatility by way of better risk-adjusted returns, but the problem is that it’s period dependent and these are very long periods.

Also, for those who use back-testing asset allocations to show how fantastic gold has been as an asset class, it must be pointed out that the repeal of Bretton Woods was a one-time event that caused gold to massively appreciate through 1974, and since so much back-testing seems to begin around 1970, it makes such back-testing very misleading.

4. Long duration government bonds

These have given a higher than average historical return from the 1970s to today due to the multi-decade bull run on bonds as interest rates fallen from 18% to 1%. The only way the returns will be the same is if interest rates continue over the next decades to come down from 1% to negative (-17)%.

This doesn’t mean they’re not useful. There is something called bond convexity, as explained here, but once again, it makes back-testing less useful.

The use of long-term government bonds depends on the purpose of your bonds. If you’re using bonds for an allocation of safe assets that you can rely on, then the high risk of long-term bonds doesn’t fit the requirement. If you’re using it as a low correlated asset class, this may be one of the best diversifiers. It will depend upon the purpose of holding bonds whether long-term government bonds are suitable.

There are two long term government bond funds available that I’m aware of.

GGOV – U.S. Treasury Bond 20+ Year ETF – Currency Hedged – has a modified duration of 16 years at the time of writing

XGOV – VanEck 10+ Year Australian Government Bond ETF – has just listed, so no information available on the actual duration yet

These funds fill a noticeable hole in the Australian market. They let you get long-term fixed interest risk, which offers excellent diversification benefits from equities. Long term bonds are technically anything over 10 years, and the long term bond funds I’ve seen vary from 13 years up to about 25 years. The longer the duration, the higher the interest rate risk, which is where the diversification benefit comes from.

For retired people, long term bond funds may not be useful since they’re often looking for asset value stability from their bond component.

But for accumulators – particularly those in funds such as VDHG – I think this would be a far better fund than the intermediate-duration bond funds they tend to use. The reason is that people using those high growth funds tend to be early in their investment journey, and the purpose of bonds in that situation is not for de-risking so much as diversification (bonds tend to go up in times of economic crisis when equities go down largely due to governments lowering interest rates in an attempt to stimulate the economy), and long term bonds serve this purpose far more effectively. Also, at that early stage of your investment lifetime, you have a long duration before you need to draw on the funds. Some all-in-one funds overseas do just this – have the 10% bonds held until around the age of 35-40 entirely in long term bonds and only begin to introduce shorter-term bonds as the bond portion of the portfolio increases to begin de-risking the portfolio.

One important issue with any new fund is the very low assets under management. Funds that are not profitable tend to get closed down, which means you are forced to realise any capital gains, and may have no alternative to move to. This is a very real risk.

5. Emerging market bonds

Vanguard has a paper on emerging market bonds and found that over the last 18 or so years, replacing some of your risky assets (stocks) with emerging market bonds improved risk-adjusted return. Whereas replacing some of your safe assets (high-quality bonds) with emerging market bonds lowered your risk-adjusted returns. So even though it’s under the asset class of “bonds”, emerging market bonds are risky and should be considered part of the risky allocation along with stocks.

Unlike stocks, bond yields are priced fairly accurately to their risk, so when you have high yielding bonds such as those of emerging market bonds, they would be comparable in risk to similar high yielding corporate bonds, where both of these offer high yields because nobody would invest in something with so much risk to get a lower return than that.

To see why high yield corporate bonds pay their higher yield, you can see how high yield bonds fared during the 2000-2002 and 2008 downturns here or more graphically here (scroll down, blue = corporate, red = govt).

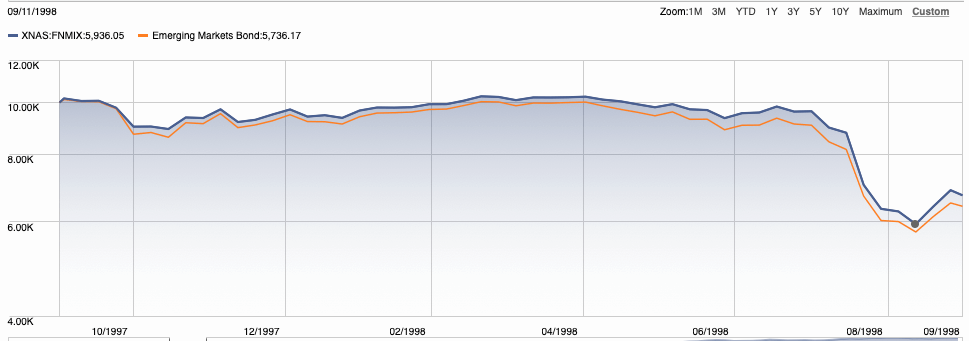

To see the risk showing up in emerging market bonds, our own emerging market fund IHEB during the coronavirus market fell over 30% in the first quarter of 2020. For another example, take a look at what happened to them during the Asian crisis of the ’90s, and you’ll see how much risk there is in emerging market bonds. They fell a massive 40 percent, as shown in the image below, which again shows you the risk is comparable to equities, not of high-quality bonds. To note the difference with high-quality bonds, since 1972 (the earliest data I could find), intermediate-term US government bonds have never had more than a 10.7% decline.

This doesn’t make emerging market bonds a poor asset class, just that you need to make sure you don’t assume it is safe just because it’s ‘bonds’, and don’t rely on it for either stability or income as you would with high-quality bonds. If you use it, use it for diversification instead, not to boost your income.

The interesting thing about emerging market bonds is that while emerging market stocks are mostly concentrated in Asian emerging markets, the emerging market bond index is vastly more diversified into non-Asian countries.

EM bonds seem like a reasonable asset class to add for diversification, but REITs, infrastructure, long term bonds, min vol stocks, value stocks, small caps, and a bunch of others would be similarly reasonable asset classes to add for diversification, but that would result in a portfolio of 10+ funds which would be a pain to manage. That’s the main reason I haven’t added most of those funds. The other is that you have to believe in these asset classes enough to hold it no matter what, because if you hold them for 10-15 years of underperformance to the rest of your portfolio (which can and does happen) and then sell it thinking it is just a crappy asset class, it would have been better to not invest in it in the first place.

Important note on tax. Since EM bonds (along with REITs, P2P lending, and high yield corporate bonds) have the majority of their return as income which miss every type of tax benefit (franking, CTG discount, ability to delay realising gains), the tax drag on returns from holding these outside super is so large that anyone not below the tax-free threshold needs to seriously consider whether it’s even worth holding them.

More info on emerging market bonds

Emerging market bonds – Bogleheads

Bogleheads emerging market google search

Final thoughts

It’s for these reasons that I’ve only discussed stocks, bonds, and cash on this site – because these each have a clearly defined use in a passive portfolio – yet the other asset classes, while great in theory, are not so clear in practice and require more domain-specific knowledge.